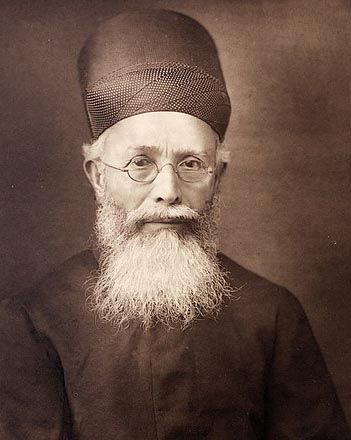

Lord Merlyn-Rees

Merlyn_Rees_appearing_on_After_Dark Open Media Ltd.derivative work: Begoon, CC BY-SA 3.0 , via Wikimedia Commons Lord Merlyn-Rees who has died at the age of 85 following a long struggle with Parkinson's Disease, was one of the last of the long line of Leeds Labour Members of Parliament who were national figures rather than local politicians. He himself followed Hugh Gaitskell, winning the by-election which was a consequence of Gaitskell's sudden death from a mystery virus, and was a constituency neighbour of Denis Healey for almost thirty years until they both retired from the House of Commons in 1992. Merlyn Rees was a popular parliamentarian, respected by colleagues in all parties. He had a friendly and open personality and was wholly unaffected by high office. For over twenty years he put up with the inevitable and pervasive presence of Special Branch detectives with patience and gratitude. They were the inevitable consequence of his years as Northern Ireland Secretary. Their attendance in Wesley Street, Beeston, where Merlyn Rees maintained a typically modest constituency residence, could never be entirely invisible but his neighbours tended to enjoy the furtive indications of their MP's presence.

Merlyn_Rees_appearing_on_After_Dark Open Media Ltd.derivative work: Begoon, CC BY-SA 3.0 , via Wikimedia Commons Lord Merlyn-Rees who has died at the age of 85 following a long struggle with Parkinson's Disease, was one of the last of the long line of Leeds Labour Members of Parliament who were national figures rather than local politicians. He himself followed Hugh Gaitskell, winning the by-election which was a consequence of Gaitskell's sudden death from a mystery virus, and was a constituency neighbour of Denis Healey for almost thirty years until they both retired from the House of Commons in 1992. Merlyn Rees was a popular parliamentarian, respected by colleagues in all parties. He had a friendly and open personality and was wholly unaffected by high office. For over twenty years he put up with the inevitable and pervasive presence of Special Branch detectives with patience and gratitude. They were the inevitable consequence of his years as Northern Ireland Secretary. Their attendance in Wesley Street, Beeston, where Merlyn Rees maintained a typically modest constituency residence, could never be entirely invisible but his neighbours tended to enjoy the furtive indications of their MP's presence.

Rees was born in Cilfynydd, Taff Vale, South Wales, the son of a miner who moved to Wembley following the 1926 General Strike. Rees studied at the London School of Economics, and then gained a further qualification at Goldsmith's College, but his entry into the teaching profession was interrupted by distinguished war service in the RAF. On demobilisation he went to teach economics and history at Harrow Weald Grammar School, where he himself had earlier studied.

Merlyn Rees' pedigree ensured that he would be active in the Labour party, and he contested Harrow East three times in the 1950s, coming within 2,000 votes of winning the seat at the 1959 by-election. On Hugh Gaitskell's death in 1963 Rees won the ensuing by-election in Leeds South and remained as MP for the area until his retirement in 1992. He then went to the House of Lords taking a title that reflected both his Welsh birthplace and his adoption by Leeds. In 1964, one year after his first election he became Parliamentary Private Secretary to the Chancellor of the Exchequer, James Callaghan, in the first Wilson government. Between 1965 and 1970 he held junior ministerial posts successively at the Ministry of Defence and the Home Office.

In 1972, following election to the Shadow Cabinet, Rees began the close connection with Northern Ireland for which he became best known, first as opposition spokesman and then, after Labour's General Election victory in February 1974, as Secretary of State. He came into office with Bloody Sunday still casting a dark shadow over the province. It was an impossible task, both from a political perspective and also from a personal point of view, with the Secretary of State having to react continually to appalling acts of terrorism and having to implement measures alien to his personality. Throughout his time in Northern Ireland Merlyn Rees maintained a civilised calmness and dependability. It was largely due to his conciliatory style and his obvious sincerity that the bipartisan attitude on Northern Ireland issues survived for so long in Parliament.

Those close to him were aware that his quiet style and disdain for rhetoric hid a warmth and a passion for justice and fairness which an occasional public comment would reveal, such as his comment in a House of Lords debate in May 1999 on protection for those giving evidence in Northern Ireland: "some of us have emotions about this matter. My father was a private soldier in Dublin in 1916. When I was studying Irish affairs in school, my father said to me, 'I realise what a mess the British Government made of it in 1916, by executing the mutineers.'"

Some commentators, both inside and outside of politics, believed that being, in Callaghan's words, "essentially a conciliator" ensured that Merlyn Rees was too gentle to be effective in Northern Ireland. The Irish writer Tim Pat Coogan said that he was "weak and faltering." The truth was that he could be tough when he needed to be - he admitted to signing personally over four hundred detention orders - but he believed that toughness in the province tended to be one-sided and to be counter productive. As he said in 1998, "there's only one way to end the violence, by talking not by killing. I was prepared to talk with anybody who was working for peace."

Merlyn Rees' biggest test in Northern Ireland came in May 1974 with the loyalist Ulster Workers' Council strike, provoked by the all-Ireland dimension of the previous government's Sunningdale agreement and aimed at bringing down the power sharing executive led by moderate unionist Brian Faulkner. Opinions then differed, and to some extent still do, as to whether the government could have faced down the strike and to have saved the executive and thus avoided direct rule. Rees' own account ten years later set out the grim reality of the developing crisis. The loyalists' control of power supplies was the determining factor and Rees made it clear that, even had it been possible to defeat the strike by force, it would not have been possible to run the power stations. He wrote, "I feel strongly that there was, and is, no way of putting down an industrial/political dispute supported by a majority in the community."

Such was Rees' standing in the Parliamentary Labour Party that it was to him alone that Harold Lever confided in December 1975 that Harold Wilson intended to resign. Rees then encouraged Jim Callaghan to stand for the party leadership and acted as his main lieutenant. When Callaghan did take over as Prime Minister from Harold Wilson in April 1976, Merlyn Rees volunteered to stay on in Northern Ireland, not only from a sense of duty but also because "I was hooked on Northern Ireland and I wanted to get back there to carry on the work of direct rule." This was despite the fact that loyalist paramilitaries had tried to assassinate him in 1974. Later, in July 1976, had it not been for Mrs Thatcher's ruling that the ending of Commons pairing arrangements applied to Northern Ireland ministers, forcing him to be in Westminster to vote, Merlyn Rees would have been in Dublin and travelling in the British Ambassador's car that was blown up by the Provisional IRA, killing the Ambassador, Christopher Ewart-Biggs, and his secretary, Judith Cook. It is probable that the IRA knew of his intention to travel with the Ambassador but were unaware of his cancellation.

Two months later Rees became Home Secretary and became increasingly drawn into difficult law and order issues linked with industrial action during the "winter of discontent". Typically, despite being a life long trade unionist, he found himself instinctively out of sympathy with union militancy and he was outspoken against pickets for their violent behaviour against the police. He was also attacked by the left for deporting Agee and Hosenball, two American journalists who exposed British intelligence secrets. The decline of the Callaghan government up to its fall in 1979 filled Rees with increasing despair. Despite, as Callaghan commented, being an amusing raconteur, Rees "would fall into a typical gloom from time to time." His essential problem was that, being a rational and fundamentally decent man, he found it difficult to understand why those with whom he dealt often had very different standards and motivations. In his "personal perspective" of Northern Ireland he comments on the pleasure of being able to spend more time with his wife, Colleen, when he ceased to be Secretary of State.

During the first Thatcher government Rees was briefly Shadow Home Secretary and then spent three years as opposition spokesman on energy. Thereafter he became somewhat of an elder statesman, serving on the Falkland Islands Inquiry Committee, becoming Chancellor of the University of Glamorgan, and serving as a trustee of the Groundwork Foundation which had projects in South Leeds. He also undertook a review of the circumstances in which an NHS "whistle blower" at Leeds General Infirmary had lost his job. On his retirement from Parliament in 1992 he became a Life Peer and played an active role in the House of Lords until Parkinson's Disease made it too difficult.

Jim Callaghan was right in saying that Merlyn Rees was "an instinctive politician" who "underrated his own strength." In one sense, as a calm and dogged conciliator, with a huge sense of duty, he was exactly the right man to take on the Northern Ireland job; but, from a different perspective, as a gentle person who much preferred the velvet glove to the iron fist, he held the job at the wrong time. In due course the historians will have the task of evaluating how much Rees' years in Northern Ireland contributed towards the eventual Good Friday agreement.

Certainly his many friends and colleagues always enjoyed his company and appreciated his obvious sincerity.

Lord Merlyn-Rees, Merlyn Merlyn-Rees, politician, born December 18 1920, died January 5 2006.

My friend David Morrish, who has died aged 86, was a committed Liberal and local politician. He combined warmth and oratory with a quick smile and a telling anecdote - all delivered in his attractive Devonian burr - which ensured his constant election over 50 years from the same community on the Exeter city council or the Devon county council. David also unsuccessfully contested nine parliamentary elections, plus one European parliament contest.

My friend David Morrish, who has died aged 86, was a committed Liberal and local politician. He combined warmth and oratory with a quick smile and a telling anecdote - all delivered in his attractive Devonian burr - which ensured his constant election over 50 years from the same community on the Exeter city council or the Devon county council. David also unsuccessfully contested nine parliamentary elections, plus one European parliament contest. Mary Ness, a stalwart of the Leeds Library has died aged 87. She joined the Library in 1992 having bought share number 382 in the days when it was still a proprietory library and before it became an open charity in 2008. Mary was a committee member from 1997 and continued as a Trustee of the charity until 2017. She was also one of the select group of library members who made loans to it to assist the purchase of the new building. She was a forthright member of the Library’s book group and was never reticent at expressing her views on books being read, or, indeed, on her fellow members.

Mary Ness, a stalwart of the Leeds Library has died aged 87. She joined the Library in 1992 having bought share number 382 in the days when it was still a proprietory library and before it became an open charity in 2008. Mary was a committee member from 1997 and continued as a Trustee of the charity until 2017. She was also one of the select group of library members who made loans to it to assist the purchase of the new building. She was a forthright member of the Library’s book group and was never reticent at expressing her views on books being read, or, indeed, on her fellow members. Leeds Honorary Alderman Brooke Nelson has died at the age of 84 after a short illness. He served as a Liberal councillor for the Armley ward from 1973 to 1983. He was a member of the Armley Common Rights Trust for some forty years, including serving as its Chairman. He also served for many years as a member of the Civic Arts Guild and the Leeds Children's Holiday Camp management committee.

Leeds Honorary Alderman Brooke Nelson has died at the age of 84 after a short illness. He served as a Liberal councillor for the Armley ward from 1973 to 1983. He was a member of the Armley Common Rights Trust for some forty years, including serving as its Chairman. He also served for many years as a member of the Civic Arts Guild and the Leeds Children's Holiday Camp management committee.

The jazz world is full of extremes of ages, from those who die criminally young such as Bix and, in the UK, Johnny Haim, to those who live - and play - into remarkable old age. Ed O'Donnell, who has died at the age of eighty-seven, was certainly one of the latter. At his death he had a programme of gigs extending well into the future.

The jazz world is full of extremes of ages, from those who die criminally young such as Bix and, in the UK, Johnny Haim, to those who live - and play - into remarkable old age. Ed O'Donnell, who has died at the age of eighty-seven, was certainly one of the latter. At his death he had a programme of gigs extending well into the future. My long-standing political colleague Mike Oborski has died at the age of 60. Michael Maciek George Oborski held dual Polish and British nationality. He maintained his contact with his Polish family and, with his wife Fran, was in Poland when its final Communist government fell. In 1996 Mike became the Honorary Polish Consul for the West Midlands. His affinity and passion for Poland and its culture was always evident in the many duties and projects he took up. A passionate European, Mike was the organiser of the "Poland Comes Home" committee which campaigned for Polish membership of the European Union and of NATO.

My long-standing political colleague Mike Oborski has died at the age of 60. Michael Maciek George Oborski held dual Polish and British nationality. He maintained his contact with his Polish family and, with his wife Fran, was in Poland when its final Communist government fell. In 1996 Mike became the Honorary Polish Consul for the West Midlands. His affinity and passion for Poland and its culture was always evident in the many duties and projects he took up. A passionate European, Mike was the organiser of the "Poland Comes Home" committee which campaigned for Polish membership of the European Union and of NATO. Jack Prichard, Labour Party activist and councillor, was the epitome of the solid, unassuming but determined Labour activist on which the party depended until the advent of new Labour and its emphasis on presentational skills attuned to the television age. Born in the Cross Gates district of east Leeds he won one of the rare scholarships to Leeds Grammar School. He went on to Leeds University where he achieved a Master of Commerce degree. He developed an early interest in politics and joined the Labour League of Youth where he met his future wife Doris.

Jack Prichard, Labour Party activist and councillor, was the epitome of the solid, unassuming but determined Labour activist on which the party depended until the advent of new Labour and its emphasis on presentational skills attuned to the television age. Born in the Cross Gates district of east Leeds he won one of the rare scholarships to Leeds Grammar School. He went on to Leeds University where he achieved a Master of Commerce degree. He developed an early interest in politics and joined the Labour League of Youth where he met his future wife Doris.