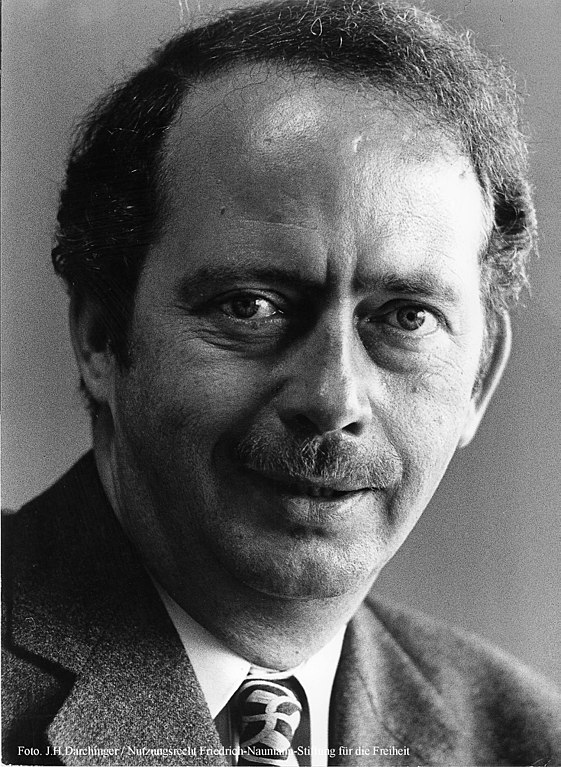

Lord Chitnis of Ryedale

The Independent obituary

Pratap Chitnis, who has died aged 77 of cancer after a short illness, was a Liberal strategist, a radical member of the House of Lords and a highly effective chief executive of a Quaker trust. He had more influence on British politics than was apparent at the time. He was always more interested in putting ideas into practice than in spending time formulating them - though it should not be thought, as has been suggested, that he was uninterested in policy and values. In fact he was deeply concerned about social values at home and about repression abroad. Every speech of his in the House of Lords and the whole thrust of the Joseph Rowntree Reform Trust's work during his twenty years as Chief Executive, was designed to diminish inequality, to protect vulnerable individuals and to ensure that the politically dispossessed achieved political influence.

Pratap Chitnis was a very conservative Roman Catholic. Born in London, of Anglo-Indian parentage, he was, at the outbreak of war in 1939, at the age of three, sent away from London into the care of nuns. From there he went to Stonyhurst, the Jesuit college. His education had a deep effect on Chitnis. and he became a deeply religious man.

He supported the Latin mass believing that it ensured that a believer anywhere in the world would be "at home." with the service. He saw no intellectual problem in being by faith a conservative catholic and by politics a radical social Liberal.

He joined the Liberal party through attending a Liberal rally at the Royal Albert Hall. Even in the dark days the party could fill huge halls. Chitnis was impressed by Jo Grimond's speech but he was so amazed that a party he thought dead and buried could pack the Albert Hall, that he joined it.

Chitnis was immediately enlisted as a candidate in the 1959 municipal elections. With five candidates from each party, Chitnis finished fifteenth and last, with precisely 98 votes. It was his first and last candidature! Four months later he was the general election agent for the Liberal candidate, Michael Hydleman, in the South Kensington constituency in which Sir Oswald Mosley stood as a fascist candidate. Hydleman was Jewish and Chitnis visibly of an Indian background. They tackled the Mosley presence head on and were duly met with an unpleasant and sometimes violent response.

Early in 1960 Pratap Chitnis was appointed as the party's first local government officer. He set about tracking down every Liberal municipal representative so that they could be mailed regularly and visited occasionally. This was less simple than it sounds. Sometimes a Liberal councillor could only be identified by contacting the local press using the devious pseudonym of the "Municipal Research Association".

The work of the department rapidly expanded and in February 1962 I joined Chitnis as his assistant. He had already been appointed as the Liberal agent for the promising by-election in Orpington. He took me to three meetings in the London to show me "what we do" and announced that he was forthwith departing to Orpington.

His role at the by-election was crucial. He designed and implemented an organisational master plan, with the basic day-to-day organisation delegated to three full-time sub-agents and took key strategic decisions, such as keeping the inexperienced candidate, Eric Lubbock, off media events with the highly articulate Conservative candidate, Peter Goldman. In addition he was decisive in grasping opportunities. The Daily Mail gave him information on the eve of poll that its opinion poll would show the Liberals narrowly ahead; he bought nine thousand copies and had them distributed to the commuters at all the railway stations in the constituency. Chitnis once told me that he had overspent the legal limit at least threefold!

To capitalise on the result the party immediately appointed Chitnis as the party's training officer and, two years later, as its press officer. Finally, in 1966, he became the party's Chief Executive.

The election of Jeremy Thorpe as party leader marked the beginning of the end of Chitnis' involvement at the heart of the organisation. He was involved in a vain attempt to stop him becoming leader, believing that Thorpe had little intellectual depth and a tendency to interfere in party affairs without authority. Pratap Chitnis' position as the head of the party's organisation became increasingly uncomfortable. In addition the party failed to follow his advice that cuts in the party's organisation were required in order to deal with the financial deficit, and, in October 1969, he resigned.

Chitnis was immediately snapped up by the Joseph Rowntree Social Service Trust (now the Joseph Rowntree Reform Trust) in York as its first professional head. It was an ideal appointment which enabled him to influence public policy without having to go through interminable party debates.

e has been described as "self-effacing" but this was not the case. A very private person, yes, but he was always happy to be known as the author of a particular policy or tactic. His marriage in 1964 to Anne Brand, an employee at Liberal headquarters, came rather out of the blue but it delighted their colleagues and friends. Their son, Simon, was born in 1966. He was a bright, intelligent boy and it was a huge blow when he developed a brain tumour. Eventually he died in 1974.

Chitnis built on the Trust's record by making it much more proactive and often controversial. It put its efforts into peacemaking in Northern Ireland and it established relations with liberation movements in southern Africa to assist them to provide administration and services in the areas that they had liberated. This latter work was the cause of a bomb arriving by post at the Trust's York office. Fortunately it didn't go off. He was also instrumental in the introduction of the so-called "chocolate soldiers" whereby bright young assistants were attached to parliamentarians. The scheme was later taken over by the government. Being conscious that many radical groups needed but couldn't afford a London base, he got the Trust to buy a large building in Poland Street in Soho so as to provide space to a host of worthy groups.

Also at this time Chitnis became a member of the Community Relations Commission and of the BBC Asian Programme Advice Committee. These appointments enabled him to claim when made a Life Peer in 1977 that it was for his services to race relations and to sit on the cross benches, even though the peerage was part of the Liberal party allocation.

In the Lords he became a defender of human rights, liberal immigration policies and, above all, an outspoken opponent of authoritarian regimes that manipulated elections. He went on election monitoring missions to El Salvador, Nicaragua, and Guatemala, and attempted to go to Guyana in 1986, only to be refused a visa by the regime. He also went to monitor the Rhodesian election of 1979. All the other monitoring bodies gave the election a favourable judgement but Chitnis condemned it, calling it "a gigantic confidence trick."

He had let his Liberal Party membership lapse in 1969 but when Jeremy Thorpe was finally forced to resign he was instrumental in persuading Jo Grimond briefly to become leader again until a successor could be elected. Then when David Steel was elected leader, Chitnis became one of his advisers, particularly assisting with his election tours. He also advised Steel during the Lib-Lab Pact of 1977-78 and during the negotiations that led to the Liberal- SDP Alliance in 1981.

He retired from the Joseph Rowntree Reform Trust in 1988 and moved to Provence with Anne, growing olives and attending daily mass. He took formal "leave of absence" from the Lords and disappointed his many friends and colleagues by virtually cutting himself off from political and social affairs and was sadly missed over the past twenty-five years.

Pratap Chidamber Chitnis, Lord Chitnis, born 1 May 1936; died 12 July 2013. He is survived by his wife Anne.

See also The Independent.

Donald Chesworth was an exceptionally able politician with the unusual characteristic of disliking intensely any sort of self promotion, only consenting to being in the spotlight when persuaded that it was unavoidable if one of his many campaigns was to be advanced. He understood the political processes superbly, and used them most effectively, but the significance of his role in postwar politics was only known to a relatively small number of colleagues.

Donald Chesworth was an exceptionally able politician with the unusual characteristic of disliking intensely any sort of self promotion, only consenting to being in the spotlight when persuaded that it was unavoidable if one of his many campaigns was to be advanced. He understood the political processes superbly, and used them most effectively, but the significance of his role in postwar politics was only known to a relatively small number of colleagues.

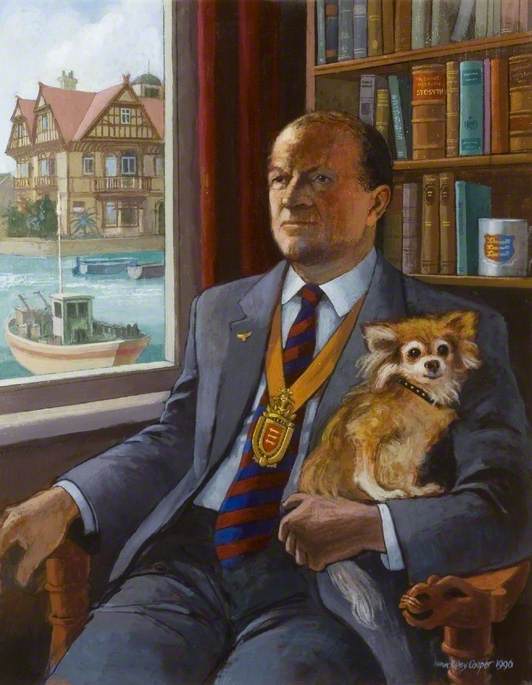

Tom was a convivial colleague and a committed Liberal who fulfilled a number of political and civic duties with dedication. He was particularly committed to the Club and in his later years he spent many weekdays in the Clubhouse even when Alzheimers had affected his memory.

Tom was a convivial colleague and a committed Liberal who fulfilled a number of political and civic duties with dedication. He was particularly committed to the Club and in his later years he spent many weekdays in the Clubhouse even when Alzheimers had affected his memory.

Gryff Evans was one of a small band of loyal and highly competent Liberals who occupied key positions within the party organisation from the mid 1960s through the '70s and who ensured that the party maintained a national presence and an effective electoral machine within the permanent constraints of finance and the electoral system. His warm personality, good judgement and conviviality guaranteed his enduring popularity with the party's rank and file.

Gryff Evans was one of a small band of loyal and highly competent Liberals who occupied key positions within the party organisation from the mid 1960s through the '70s and who ensured that the party maintained a national presence and an effective electoral machine within the permanent constraints of finance and the electoral system. His warm personality, good judgement and conviviality guaranteed his enduring popularity with the party's rank and file. Joan "Penny" Ewens, Honorary Alderman and former Leeds City Councillor, has died at the age of 94. Her maiden name was Penwill which gave rise to the name Penny at her Liverpool school to differentiate her from five other Joans in the same class. She served in the Intelligence Corps during the war and met her future husband, David Ewens, on VE day in London. They were married soon afterwards. David's job brought them to Leeds in 1960 and, as a mature student, she enrolled at the James Graham Teacher Training College. After a spell at the Kitson College she settled into a long career at West Park High School where she took a particular interest in careers and in drama.

Joan "Penny" Ewens, Honorary Alderman and former Leeds City Councillor, has died at the age of 94. Her maiden name was Penwill which gave rise to the name Penny at her Liverpool school to differentiate her from five other Joans in the same class. She served in the Intelligence Corps during the war and met her future husband, David Ewens, on VE day in London. They were married soon afterwards. David's job brought them to Leeds in 1960 and, as a mature student, she enrolled at the James Graham Teacher Training College. After a spell at the Kitson College she settled into a long career at West Park High School where she took a particular interest in careers and in drama.