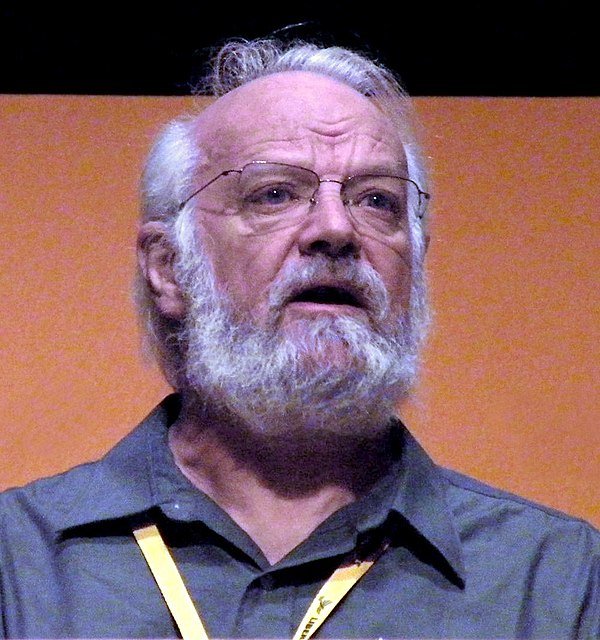

Lord Andrew Stunell

Journal of Liberal History obituary

Official portrait of Lord Andrew Stunell Photo: Chris McAndrew, CC BY 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Official portrait of Lord Andrew Stunell Photo: Chris McAndrew, CC BY 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Andrew Stunell combined a commitment to Liberal values with a highly practical negotiating skill. He initially came into Liberal politics through a single issue: the Harold Wilson government reneging on its guarantee to the Kenyan Asians to admit them to Britain if the post-independence Kenyatta government expelled them. When, in 1968, their expulsion happened, the Labour government passed a new Commonwealth Immigrants Act to restrict drastically their entry to the UK. Though from a family that frowned on political activism, the ground for his political response was prepared by his non-conformist commitment to his local Baptist church which had already led to him being involved in international development projects. Like others who joined the Liberal party on a single issue of principle, Stunell found the party a congenial home, well suited to his personality.

Stunell always saw his aptitude as being in the practical application of his beliefs rather than the intellectual development of philosophy and policy. That practicality was evident even from his choice of architecture as his university courses and, when he had a professional post in Runcorn New Town Development Corporation, he was active in his trade union, NALGO, and spent four years as staff side representative negotiating on the Whitley Council for New Towns. Living at the time in Chester he was elected to the city council in 1979, serving there for eleven years, and to the Cheshire county council from 1981 to 1991. On the latter he immediately became the Liberal Alliance group leader and was thrust into the difficult practicalities of a hung council. Typically Stunell, having concluded a modus operandi for Liberal Alliance involvement in the governance of the council, enshrined this in a document which became known as the “Cheshire Convention”. It was subsequently used as the model for ensuring the effective administration of councils with no single party control.

Stunell contested his local Chester parliamentary constituency three times , in 1979, 1983 and 1987. It was an uphill task, not least being a Labour/Conservative marginal, but he increased the Liberal Alliance vote on each occasion - in 1987 against the national trend. In 1989 he was persuaded to put his name forward for the candidature in the Hazel Grove constituency, just twenty miles from Chester. This was much more promising Liberal/Conservative marginal and had been held briefly between the two 1974 elections by the charismatic GP, Michael Winstanley. Stunell was duly adopted and at the 1992 election slightly increased the party vote - again against the national trend - but failed to gain the seat by just 929 votes. He then committed himself fully to the constituency, moving there from Chester with his family. He had given up his architectural practice in 1985 to work full time for the Association of Liberal Democrat Councillors and this gave him rather more freedom for politics. Knowing well the electoral advantage of a presence on the local council, in 1994 he fought and won a seat on the Stockport Metropolitan Borough Council. At the 1997 parliamentary election Stunell gained the Hazel Grove seat with an almost 12,000 majority and a swing way ahead of the party’s national performance. It was the culmination of eight years careful planned campaigning; and significantly by the time of the 1997 election Liberal Democrats held every seat in the Hazel Grove constituency on the Stockport Council. Like many Liberals, Stunell had sacrificed financial advancement in order to concentrate on his politics and, as a consequence, he was astounded at what he regarded was a high MP’s salary. Typically he had never bothered to find out the pay and, when he was informed of the amount, he called his wife, Gillian, and said to her “we’re rich!”Similarly, never having taken himself too seriously, he happily involved himself in the practical tasks at his local Methodist church.

Immediately following the 1987 general election, at which the two Alliance parties had dropped back compared with 1983, albeit only slightly1, David Steel bounced the parties into moving towards merger and at the Harrogate Liberal Assembly in September that year delegates recognised his negotiating experience in local government and appointed Stunell (and also myself) to the eight members directly elected to the negotiating team.2 His first action was to draft a paper for the first meeting of the Liberal team. This set out the “issues that must be settled by the team prior to substantive talks with the SDP” (Stunell emphasis). The paper went on to set out many of the pitfalls ahead “into which the team subsequently fell”; he also called for an analysis of the weaknesses and strengths on both sides, “Unfortunately this never took place”. 3 Later in the negotiations, when members of the team were speculating on whether amendments to the final documents should be debated if the [Liberal] Assembly did not vote for merger, Stunell was decisive stating that the Assembly was sovereign and that “merger needs the Assembly’s massive support”.4 Throughout the negotiations Stunell was unflappable and played a significant role, even though at one point he alarmed colleagues by stating that he was less concerned about the aims of merger than the processes of negotiation.

Immediately on Stunell’s election the then party leader, Paddy Ashdown, aware of his particular skill made him Deputy Whip. It is clear that Ashdown had a high regard for Stunell’s loyalty and for his ability to defuse internal dissent and that he would act professionally even when he personally disagreed with the line being promoted.5 Ashdown’s successor, Charles Kennedy promoted Stunell to Chief Whip in 2001 and he continued in that post until the end of Kenney’s leadership in 2006. Under his stewardship as Chief Whip every Liberal Democrat voted against the March 2003 invasion of Iraq - the only party to do so unanimously - even before the absence of the assumed weapons of mass destruction became apparent. A year later he headed the Private Members’ ballot and successfully steered through the Commons an act designed to make new buildings greener and safer. Stunell was also concerned at the way new MPs were expected to cope in a complex procedural and political environment and was instrumental in getting induction courses set up for later intakes. As Chief Whip Stunell was “hiding a disturbing secret: the Leader [Charles Kennedy] was drinking heavily and it was beginning to affect his performance. [The party] made it through without it becoming public, but the whispers grew louder, and eventually Mr Kennedy was ousted in a putsch by the party’s MPs.” Stunell admitted that “behind the scenes things were difficutl.”6 For over four years, during almost the whole of Stunell’s period as Chief Whip, the problem of Kennedy’s alcoholism had hovered over the party’s fortunes and required considerable smounts of his time trying to resolve internal tensions not least to hide the situation from the media. Inevitably there were those who felt he had “failed to grasp the scale of their anxieties.”7 By December 2005 Stunell could not have been unaware of the inevitable outcome of Kennedy’s ill health having received a “devastating aide-memoir” fro Chris Rennard, the party’s Chief Executive, setting out that Kennedy’s position was untenable.8

As is invariably the case with smaller parliamentary parties, Liberal Democrat Members have to take on subject responsibilities and Stunell was spokesman on Energy (1997-2006) which tied in well with his architectural qualifications and experience, and on Communities and Local Government (2006-08). He was also Chair of the local election campaign team, 2008, and vice-chair of the general election campaign team, (2009-10). In late 2009, some six months before the anticipated date of the general election, the Liberal Democrat leader, Nick Clegg, set up a highly confidential internal group to prepare for the eventuality of the party having the balance of power. In addition to Stunell, its members were Danny Alexander, Chris Huhne and David Laws.9 Stunell welcomed this initiative particularly as he was critical of the Liberals’ involvement in the Lib-Lab pact of 1977-78, stating: “as someone who had been on the outside at that point, all my experience in local government showed that the Liberals had completely misplayed their hand in that Lib-Lab pact.”10 By preparing in advance in early 2010 they were able to establish what type of inter-party co-operation was vital and what should be the party’s priorities therein.11 It was clear that Stunell was not only regarded as having negotiating experience in the local government sphere but also could play the role as a trusted link between the parliamentary party and the party in the country. There were inevitably great pressures on the party leadership, including Stunell as Chief Whip, to make the key decision on coalition, not least because the financial markets were very febrile, but Stunell counselled caution. Speaking on the Sunday afternoon, after just four days of intensive sessions with the Liberal Democrat parliamentary party and party officials and with both Labour and Conservative parties: “we are all very tired. We need to take a deep breath and get this right. And we need to realise that from a public and media perspective there is a real, real difficulty legitimising Labour after they have lost the election so badly.”12

In the negotiations with the Labour team it was Stunell who kept stressing the importance of constitutional reform, for instance proposing setting up a new Commons committee to undertake the time tabling of government business. 13 At the next meeting with Labour Stunell is reported as asking “bluntly” how serious Labour was about delivering its negotiation commitments and “what guarantees it could give.14 Then, being described as a “wiry persistent man, he had irritated Peter [Mandelson] with his aggressive pointmaking and minilecture on the elective dictatorship” all of which provoked Mandelson to ask his colleagues, “Who is he?” Andrew Adonis had to inform Mandelson that Stunell was an ex-local government leader and had a reputation as the Lib Dem expert in coalition-mongering in hung local authorities.”15 Stunell was certainly persistent in the discussions with Labour, telling a later meeting that they needed to “get real” and to “raise your offer considerably if [they] wanted to ‘stay in the game’”. This again annoyed Peter Mandelson who texted Danny Alexander during the meeting, asking whether Andrew “might be a bit more civil so we could make progress”!16

He later commented on the negotiations:

“It wasn’t at all clear it would always be the Conservatives. The arithmetic was a real tease because if you added us and Labour together we would not have had an overall majority and therefore would have required either the active or passive support of another party. We had a discussion with the Labour Party in which we did point this out to them. They were very gung ho about us joining them, but I think they thought what they could get was a Lib-Lab pact, like it had been in 1978, where basically the Liberals simply went along with Labour in the Callaghan government.17

“When we said ‘The numbers don’t add up,’ they said ....’Don’t worry, we’ve got the nationalists’. Had any other basis for a deal been there then we might have explored what they meant by ‘We’ve got the nationalist.’”18

By contrast Stunell found the Conservatives “were falling over themselves to give the Liberal Democrats what they wanted. ... It would have been a pretty odd situation to have then turned away and said that’s not good enough.”19

He was immediately appointed as Under-Secretary in the Department of Communities and Local Government in which ministerial capacity he was responsible for what became the 2011 Localism Act which devolved a number of powers from central to local government. However, after just two years in post he was a victim of a reshuffle in July 2012, along with Sarah Teather, Nick Harvey and Paul Burstow. The reason given by Nick Clegg was that he wanted to give other deserving Liberal democrat MPs “a place in the sun” before the end of this parliament. In fact it was also to enable David Laws to return to government as Minister of State for Schools and also the Cabinet Office.20

Stunell was awarded the OBE in 1995 for political service and was knighted in 2013. He was made a member of the Privy Council in 2012. He was created a Life Peer in 2015 following his retirement from the House of Commons. In the Lords he served on the Committee on Standards in Public Life, 2016-2022. As the party’s spokesman in the Lords on the Construction Industry, he accepted an invitation by Lord Newby, the party leader, to review the impact of Brexit on the construction industry.

Robert Andrew Stunell, Lord Stunell, born 24 November 1942; died 29 April 2024

References

1. Liberal party down by 1% and the SDP down by 2%.

2. Details of all matters relating to the inter-party negotiations regarding the merger between the Liberal and the Social Democratic parties are to be found in Merger - The Inside Story, Rachael Pitchford and Tony Greaves, Liberal Renewal, 1989.

3. Op cit pp 16/17.

4. Op cit pp 138/139.

5. See eg Ashdown Diaries, Volume II, Allen Lane Penguin Press, 2001, entry for 22 July, p 70; also entries for 22 October 1998, p 303; and for 10 November 1998, p 330.

6. Article, Rosa Prince, 25 April 2015, Daily Telegraph.

7. Charles Kennedy - A Tragic Flaw, Greg Hurst, Politicos 2006, pp 189 and 252; Hurst’s book is the source of much of the material on this period.

8. Hurst op cit, appendix E.

9. Politics Between the Extremes, Nick Clegg, The Bodley Head, 2016, p 175; Nick Clegg - The Biography, Chris Bowers, Biteback, 2011, p 223; 22 Days in May - The Birth of the Lib Dem - Conservative Coalition, David Laws, Biteback 2010, pp 14 et seq.

10. Op cit Daily Telegraph article.

11. David Laws’ 22 Days in May is important on this subject, pp 15-22.

12. Coalition, David Laws, Biteback 2016, pp 12-13.

13. 5 Days in May - The Coalition and Beyond, Andrew Adonis, Biteback, 2013, p 47

14. Adonis op cit, p 49.

15. Adonis op cit, p 50.

16. Adonis op cit, p 115.

17. For this period see: The Lib-Lab Pact - A Parliamentary Agreement, 1977-78, Jonathan Kirkup, Palgrave MacMillan, 2016; A House Divided - The Lib-Lab Pact and the Future of British Politics, David Steel, 1980; The Pact - The Inside Story of the Lib-Lab Government, 1977-78, Alastair Michie and Simon Hoggart, Quartet, 1978.

18. Daily Telegraph 2015 interview op cit. In fact Douglas Alexander stated publicly at the time that “Under no circumstances will we work with the SNP”.

19. Daily Telegraph, 2015, op cit.

20. Daily Telegraph, 2015, op cit.

My political colleague, Richard Stokes, has died at the age of 100. Richard was a brilliant politician who only achieved an executive position at the age of 81 when he became the leader of Slough Borough Council as the Liberal head of a four party coalition. Born in Southport to Richard, a commercial traveller, and Leonora, (neé Sancto) he was brought up as a socialist. He was a loyal but somewhat wayward Labour party member, initially in Southport, where he began work as a junior clerk with the Southport Corporation. In 1940 he volunteered for the RAF and became a Radio Navigator. After the war he went to Manchester University where he obtained a BA in Social Administration. In 1950 he joined the Royal Cotton Commission, as a welfare and personnel officer. He followed this as a management appointments office with Littlewoods, Liverpool, Personnel Manager at Glaxo in Brentford, and Group Personnel Director for the Burton Group in 1974 in London, before becoming self-employed, based in Slough.

My political colleague, Richard Stokes, has died at the age of 100. Richard was a brilliant politician who only achieved an executive position at the age of 81 when he became the leader of Slough Borough Council as the Liberal head of a four party coalition. Born in Southport to Richard, a commercial traveller, and Leonora, (neé Sancto) he was brought up as a socialist. He was a loyal but somewhat wayward Labour party member, initially in Southport, where he began work as a junior clerk with the Southport Corporation. In 1940 he volunteered for the RAF and became a Radio Navigator. After the war he went to Manchester University where he obtained a BA in Social Administration. In 1950 he joined the Royal Cotton Commission, as a welfare and personnel officer. He followed this as a management appointments office with Littlewoods, Liverpool, Personnel Manager at Glaxo in Brentford, and Group Personnel Director for the Burton Group in 1974 in London, before becoming self-employed, based in Slough. Trevor Smith, who has died aged 83, was an influential figure in Liberal/Liberal Democrat and academic circles for 60 years, more as a "fixer" than as a frontline player. After an early involvement in electoral politics he was appointed a politics lecturer at Hull University in 1962, and rose to become vice-chancellor of Ulster University (1991-99). Throughout he stayed with his party and from 1997 was active as a life peer.

Trevor Smith, who has died aged 83, was an influential figure in Liberal/Liberal Democrat and academic circles for 60 years, more as a "fixer" than as a frontline player. After an early involvement in electoral politics he was appointed a politics lecturer at Hull University in 1962, and rose to become vice-chancellor of Ulster University (1991-99). Throughout he stayed with his party and from 1997 was active as a life peer. For many years Eric Syddique's name was synonymous with the campaign for electoral reform and he served on the staff of the Electoral Reform Society for many years, taking over from the formidable Enid Lakeman as its secretary. He was a lifelong Liberal and later Liberal Democrat. He was elected six times to the Sevenoaks District Council from 1973 until he retired in 1995. He was also a member of the Eynsford Parish Council and served as Justice of the Peace for the County of Kent. He also served as Chairman of the Lewisham and Kent Islamic Centre.

For many years Eric Syddique's name was synonymous with the campaign for electoral reform and he served on the staff of the Electoral Reform Society for many years, taking over from the formidable Enid Lakeman as its secretary. He was a lifelong Liberal and later Liberal Democrat. He was elected six times to the Sevenoaks District Council from 1973 until he retired in 1995. He was also a member of the Eynsford Parish Council and served as Justice of the Peace for the County of Kent. He also served as Chairman of the Lewisham and Kent Islamic Centre. I was sorry to hear of Harry Swain's sudden death. I bumped into him in Leeds City Centre earlier this year and briefly passed the time of day. I wish now that we had talked more.

I was sorry to hear of Harry Swain's sudden death. I bumped into him in Leeds City Centre earlier this year and briefly passed the time of day. I wish now that we had talked more.