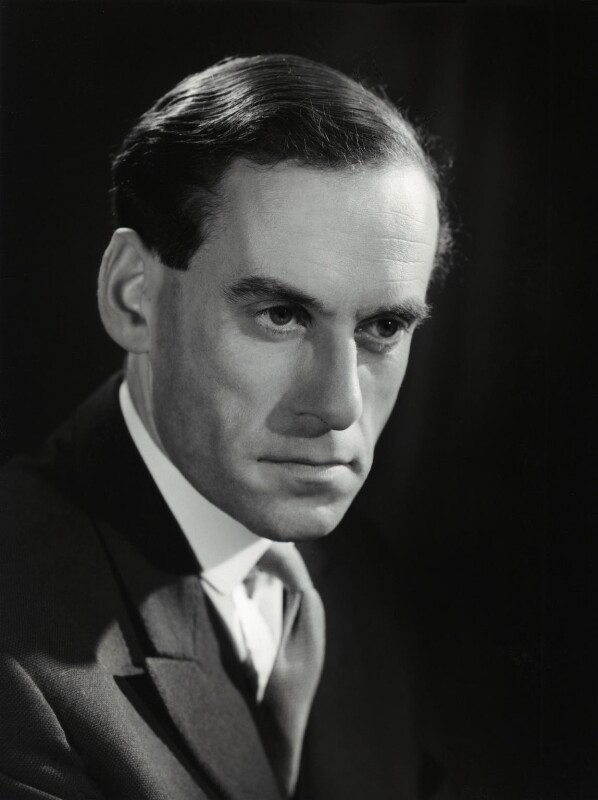

Jeremy Thorpe, by Walter Bird, NPG x167152An assessment of Jeremy Thorpe the politician and of him as the Liberal Party leader for nine years is bedevilled by the huge shadow of the eventual public revelations of his sexuality and the attempts to conceal it over almost his entire parliamentary life, followed by the lurid details of his trial for attempted murder. These latter events are relevant to an evaluation of his career only insofar as they affected his and his colleagues' ability to promote effectively the Liberal cause. Quite apart from Michael Bloch's much reviewed biography - which is very good on Thorpe the person if somewhat naïve on the political aspects - there is by now considerable evidence on the record of his defects and of his lack of political judgement, but throughout the years of his leadership the criticisms and frustrations of those running the party were inevitably muted by an awareness of the electoral consequences of undermining the leader whilst in office. Mine was a fairly minor role in the early days but the loyalty and forbearance of key party officers such as Gruffydd Evans, Geoff Tordoff and Tim Beaumont meant that the problems were hidden from the mass of the party until the events of the party Assembly in Southport in September 1978, to which I will return.

Jeremy Thorpe, by Walter Bird, NPG x167152An assessment of Jeremy Thorpe the politician and of him as the Liberal Party leader for nine years is bedevilled by the huge shadow of the eventual public revelations of his sexuality and the attempts to conceal it over almost his entire parliamentary life, followed by the lurid details of his trial for attempted murder. These latter events are relevant to an evaluation of his career only insofar as they affected his and his colleagues' ability to promote effectively the Liberal cause. Quite apart from Michael Bloch's much reviewed biography - which is very good on Thorpe the person if somewhat naïve on the political aspects - there is by now considerable evidence on the record of his defects and of his lack of political judgement, but throughout the years of his leadership the criticisms and frustrations of those running the party were inevitably muted by an awareness of the electoral consequences of undermining the leader whilst in office. Mine was a fairly minor role in the early days but the loyalty and forbearance of key party officers such as Gruffydd Evans, Geoff Tordoff and Tim Beaumont meant that the problems were hidden from the mass of the party until the events of the party Assembly in Southport in September 1978, to which I will return.

One should start any obituary of Jeremy Thorpe by stating the positives. Coming from a strongly Conservative family he joined the Liberal party whilst a student at Oxford for exactly the right reasons: industrial co-ownership, the statutory ending of monopolies, civil liberties, colonial freedom and electoral reform. He opposed the Suez invasion, and in parliament he opposed capital punishment, supported abortion law reform and homosexual law reform - none of which would be likely to be likely to go down well with his constituents. He maintained his key principles throughout his life. He was adopted as the candidate for North Devon in 1952 at the age of 23, just one year after the worst Liberal general election result ever. The problems with Thorpe were to do with the outworking of his beliefs and with the lack of a strategic ability to make them effective. Part of the reason for this was an apparently innate lack of respect for the party nationally and a consequent inability to regard it as a partner in the task of promoting Liberalism. He certainly had charisma and an ability to charm individuals and to make excellent speeches, often with a compelling turn of phrase, but the concern was whether there was anything more than the showman who enjoyed the aura of high society and of sometimes indulging in student-like japes. There is, for instance, no book, booklet or pamphlet written by him in his nine years as party leader. There was also a certain illiberal sense of social superiority, presumably stemming from his background and his education, which from time to time would show in disparaging treatment of party staff and even of a belief that he was entitled to sack an individual whose work he felt inadequate.

It took him seven years intensive work in the constituency to win North Devon in 1959 and, being the only Liberal gain in that election, it heartened and enthused the whole party. He held the seat for twenty years until the publicity surrounding the criminal charges he faced, and the impending court case, brought his defeat in 1979. In contrast to his relationship with the party at national level, he had a warm affinity with his electors and he evinced a remarkable ability to recall individuals and their interests on subsequent meeting.

The question for party officers in 1967 was whether the flamboyant showman, with Liberal instincts but some dubious friends, would be the best leader for the party following Jo Grimond's retirement. Jo would have been a hard act for anyone to follow. Intellectually secure, the writer of two full length books and many pamphlets on Liberalism, the catalyst for attracting thinkers and academics as well as members and candidates, an inspiring platform speaker and television performer, he almost singlehandedly made a party with a minuscule parliamentary presence politically relevant as a non-socialist party seeking a realignment of the Left. Jo had always said "get on or get out" and had given the party ten years to do it. He followed his own advice and indicated his intention to retire at the end of 1966. Efforts to dissuade him failed and, in reality, those of us who worked closely with him were conscious of his increasing unwillingness to take on party meetings and rallies.

In key respects Jeremy Thorpe was the exact opposite of Jo Grimond, embracing gimmicks, flashiness and a risky personal life, whereas Jo would refuse to do "photo opportunities" saying to me that "politics is too serious for gimmicks". And Jo was certainly not a flashy dresser but usually slightly scruffy in an acceptably eccentric way! Retiring when he did limited the potential candidates for the succession, effectively ruling out MPs only elected nine months before, including amongst those who could conceivably have harboured ambitions, John Pardoe, James Davidson, Michael Winstanley and, crucially, Richard Wainwright. Russell Johnston and David Steel had a little more seniority but did not at that point come forward. Peter Bessell was bound to support Thorpe, his west country colleague. Those "party managers" who believed that Thorpe was politically shallow and personally risky, including Gruffydd Evans, Tim Beaumont and Pratap Chitnis - and, apparently, Frank Byers, though I was unaware of it at the time - had a dilemma. They had, rightly, kept their doubts about Thorpe away from the party generally and had no legitimate means of inhibiting his candidature.

There was a further question mark against Thorpe. He had become the party's treasurer in October 1965. The party was in one of its perennial financial crises and Thorpe tapped a few big donors in order to bale out the party. Thorpe and cash were a continual problem and from 1961 he had personal access to funds which he was able to use tactically to develop his stature within the party. It eventual led to the resignation of Sir Frank Medlicott as party treasurer in 1971. Sir Frank told me at the time that he "was not prepared to be treasurer of a party in which the party leader controlled secret funds." Loyally Sir Frank publicly gave ill health as the reason for his resignation and he did, indeed, die shortly afterwards.

Neither eventual leadership candidate against Thorpe had enough salience. Emlyn Hooson was regarded as right wing and out of sympathy in the party as a successor to Grimond's whole realignment strategy whilst Eric Lubbock was a fine "fixer" but not charismatic enough to be leader. Even so, the headquarters "cabal" made one last attempt to thwart Thorpe, by running Wainwright, entirely without his connivance, or even knowledge, as a possible additional candidate. There was only one full day between nominations and the election by the twelve MPs but even so "soundings" were taken. As Local Government Officer, my instructions from Pratap Chitnis, as head of the party organisation, were to telephone every council group leader and ask, given the three candidates, which they would favour. Almost without exception they named Jeremy Thorpe. I would then ask what their view would be "if Mr Wainwright was a candidate"; almost invariably the answer was the same. The same response was forthcoming from the other party groups consulted - candidates, Women's Liberal Federation members and Young Liberals. The latter came to regret that opinion a few years later.

The first ballot gave Thorpe six out of the twelve votes, whereupon Emlyn Hooson and Eric Lubbock withdraw from a second ballot thus giving Thorpe an unopposed election. The leadership die was thus cast and the party walked the tightrope of Thorpe's political and personal adventurism thereafter. Peter Bessell was regularly engaged in keeping Thorpe's gay lovers at arms length and, unlike Jo Grimond who managed to engage with the radical excesses of the Young Liberals, Thorpe naively supposed that he could discipline and stifle them and he thus managed to have a public falling out. Other important groups both in and out of the party were also increasingly frustrated by his lack of depth and as early as January 1968 Tim Beaumont and the four other original dissidents, plus Richard Holme, were discussing whether or not it was possible to engineer his resignation. The continuing problem was the lack of a viable alternative. Richard Wainwright's name was continually mentioned and that autumn Richard asked William Wallace and me to see him at his Leeds home. He instructed us to stop promoting his name saying that he was not a leader. Leadership required a "first thinker" capable of virtually immediate sound analytical judgement on issues whereas he was a "second thinker" whose skill was to consolidate and develop.

Jeremy Thorpe's out of the blue wedding to Caroline Allpass on 31 May 1967 only partially muted the criticisms, although the dissident quintet made an ill-timed strike whilst they were on their honeymoon. Obviously Thorpe was perfectly entitled to celebrate his wedding any way he wished but the ostentatious and establishment laden festivities jarred with radical colleagues. Thorpe had never been able to command the warm support of the party as a whole and for the rest of the parliament he struggled with criticism from a number of influential individuals and from Young Liberals whilst receiving loyal support from a bewildered membership. At this time the young Liberals were a numerous and intellectually radical force and Thorpe could have harnessed their enthusiasm and commitment to radical causes but instead he chose to take them on. Ironically, one of the Thorpe "ideas" that they applauded - the suggestion that rail lines into Ian Smith's Rhodesia could be bombed to deny him supplies - was actually planted on him by a South African BOSS agent with a view to discrediting the Liberal party. Once Thorpe had made the speech, the agent returned to South Africa.

Following the leadership election there was little evidence of an electoral honeymoon and a year after his election as leader the party had gained just one percentage point. 1968 was a year of missed opportunity. With Labour at its lowest rating since polling began - it dropped to 28% in the middle of the year - the party could have mounted a determined and focussed national appeal to disillusioned Labour voters, just as was done in some localities, but the leadership had no real awareness of how to tackle traditional Labour areas and the chance passed.

The single bright spot came the following year with the party's by-election gain in Birmingham in June 1969 but this was a personal victory for the candidate, Wallace Lawler, who had been a popular local councillor for seven years. At the following general election, in 1970, the party vote was down slightly on 1966 and Thorpe's own majority in North Devon dropped to a perilous 369.

Throughout this whole period the spectre of Thorpe's homosexual liaisons, illegal at the time, hovered over him and also, by association, his close friend Peter Bessell, MP for the neighbouring Bodmin constituency who, in order to stave off potential disaster, was making regular payments to one such, Norman Scott, who had also managed to contact Caroline by telephone. Whereas Thorpe showed no external sign of the turmoil of his personal life, it must surely have had a detrimental effect on his - and Bessell's - political judgement and capacity. As if these political and personal problems were not enough, just two weeks after the 1970 election polling day Caroline was killed in a car accident when driving back to London from North Devon. There were hints that she was distracted by some fresh development in the Scott saga but the more plausible explanation was that she was momentarily distracted through being extremely tired from the election campaign and from looking after the Thorpes' young son.

Not surprisingly Thorpe was devastated and for some eighteen months was only able to carry out the minimum of duties so that the party staggered on lacking firm leadership with poll ratings hovering around 6-7% through 1970 and 1971 and fighting only six of the fourteen by-elections - coming third in each one. The most significant initiative was promotion of the community politics strategy mainly by young Liberals, which was formally adopted by the party at its 1970 Assembly and towards which Jeremy Thorpe was decidedly lukewarm. In 1972 there were a number of parliamentary issues on which Thorpe made a positive Liberal contribution. First, he led the Liberals into the government lobby to save the day against an anti-EU proposition from Enoch Powell which split the Tories; second, he opposed the Rhodesia deal Sir Alec Douglas-Home had reached with Ian Smith on behalf of the government; third, he opposed the support being given to the Stormont Assembly on internment; finally, he supported the right of the Ugandan Asians being expelled by Idi Amin to come to Britain. On all four issues the government eventually adopted Thorpe's Liberal line. The electoral tide began to turn for the party in 1972 partly through the happenstance of a by-election in Rochdale won, as in Birmingham Ladywood, by a popular local councillor, Cyril Smith, with the active personal support of the party leader.

A by-election in Sutton and Cheam, eventually in December 1972, had been trailed since June when it was known that the Conservative MP was to be appointed as Governor-General of Bermuda. It was regarded as a safe Conservative seat and the Liberal candidate had finished a poor third in 1970. However, at the September party assembly. Trevor Jones, Deputy Leader of Liverpool Liberals, and a enthusiast for "community politics" easily defeated Penelope Jessel, the leadership's candidate for the party presidency, and he moved into Sutton and Cheam with his "Focus" leaflets and immense enthusiasm. The Liberal, Graham Tope, took the seat with a majority of 7,000. The victory had little to do with the party leader, and Trevor Jones led the subsequent by-election campaigns to substantial second places in unlikely places, such as Manchester Exchange and Chester-le-Street, neither of which the party had even fought in 1970. The momentum lifted the poll ratings to 22% and enabled the gains in Ripon, the Isle of Ely and Berwick. Meanwhile Jeremy had married Marion, divorced from Lord Harewood, the Queen's cousin, six years earlier. The wedding celebrations attracted the same comments as the earlier ones had but there was no doubt as to the pleasure the marriage brought them both.

The party went into the February 1974 general election in extremely good heart. Given his narrow majority at the previous election, Thorpe decided to stay in his constituency for the whole campaign, broadcasting nation wide from a makeshift studio in the board room of the Barnstaple Liberal Club. The opinion polls showed that he scored over the other leaders and it was thought that staying out of the rough and tumble had in fact helped the Liberal campaign. A great deal has been written on the immediate post-election negotiations with Edward Heath on the possible formation of a coalition. There was no doubt that Thorpe wanted to be in office - going to see Heath without consulting anyone in the Liberal party is a strong hint - but it was never a possibility given the arithmetic and the political reality. What would have happened had it had been possible, given what was known in security files on his background, remains an interesting speculation.

With six million votes and almost 20% of the poll, and a Labour minority government, it was clear that there would be a second election within months. The party, and its leader, were clearly popular and all the local activists would have responded to the leader launching a barnstorming crusade across the country. Alas, it didn't happen and a huge opportunity was lost, with the leader apparently preoccupied with his personal problems and, later, bogged down in the risible failure of his hovercraft gimmick. Instead of achieving a breakthrough, and despite fighting all but four British seats - at last realising John Pardoe's long campaign - the vote dropped, in real terms, by five per cent. There was mounting criticism of Thorpe from within the party, muted only by the three month European referendum campaign in which Thorpe played a significant and positive role in securing the pro-EU vote in June 1975.

Thereafter it is the record of Thorpe's long delayed descent into the depths of the scandal, the court case, the eventual reluctant resignation as party leader and the loss of his seat in 1979, punctuated by further examples of his poor judgement and manipulation. The collapse in 1973 of the somewhat shady London and Counties Securities secondary bank, with which he had got involved on the advice of a close friend and advisor, led to trenchant criticism from the two inspectors who investigated its failure. The personal introduction in 1977 of a crook, George de Chabris, real name George Marks, to the National Liberal Club which he asset stripped mainly for the benefit of himself and his family. And the obtaining of a great deal of money from Jack Hayward, including considerable sums under false pretences and on occasion diverted to uses other than for which Hayward had given it - including amounts to buy incriminating documents from Norman Scott. It is all a very sad story and it is only surprising and, in a way, a relief that it took so many years for the simmering pot to boil over. As Michael Bloch's biography makes clear, Thorpe carried on a dangerous double life that at any point could have seriously damaged the party. I remember vividly the embarrassment of canvassing at the 1979 election when the party leader was on a charge of the attempted murder of his homosexual lover. No wonder we did so badly on polling day.

As was their right, none of the principal defendants chose to give evidence at the trial. Whether, had they done so, given what has emerged since, not least from the late David Holmes, the jury's verdict would still have been for acquittal must be in doubt. Nevertheless, what was disclosed and accepted was quite sufficient to discredit Thorpe.

As party officers realised at the 1978 party Assembly at Southport, even so late in the day, most party members were unaware of the history. Thorpe had promised David Steel, newly installed as party leader, that he would not attend. He insisted on arriving in style and effectively hijacking the proceedings for his own selfish purposes. He was publicly criticised at the Assembly and a very loyal Liberal candidate from Hove, Dr James Walsh, put down a motion of censure of the party officers for their treatment of Jeremy Thorpe as leader. The three key officers at Southport, Gruff Evans, president, Geoff Tordoff, chair, and myself, Assembly committee chair, were furious and decided to take the motion head-on at a closed session of delegates. All three of us agreed that if the motion was carried we would resign on the spot. Gruff opened the proceedings with a forthright detailed exposé of Thorpe's actions and behaviour extending from before he became leader. The delegates were astounded and Dr Walsh was very distressed at what he had caused. In the end the motion was not put and the damaging resignations avoided. Thus ended Jeremy Thorpe's career within the Liberal Party. Lots of froth, a great deal of posturing, a curious fondness for high society, an inability to conduct potentially damaging liaisons discreetly, a willingness to manipulate individuals for his own survival, a regular refusal to accept political advice and a lack of political depth and judgement. Not a great CV for a Liberal Leader.

Even so no-one would have wished on him the physical debility of over twenty five years of Parkinson's Disease nor the indignity of being made to leave his home of thirty years having been made to move out last March following Marion's death as the Orme Square house was personal to her following her divorce.