An appreciation written for the Journal of Liberal History, 102, Spring 2019

by Michael Meadowcroft

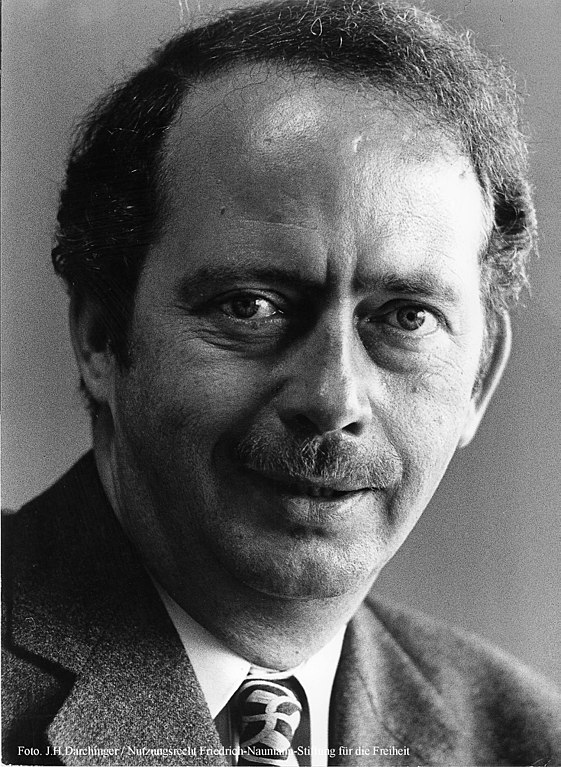

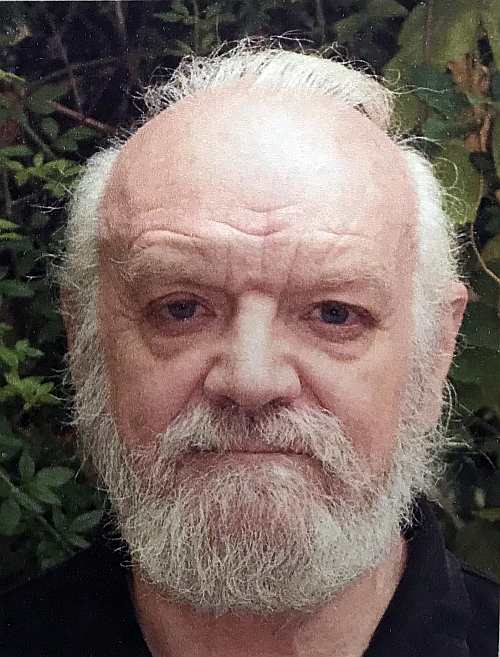

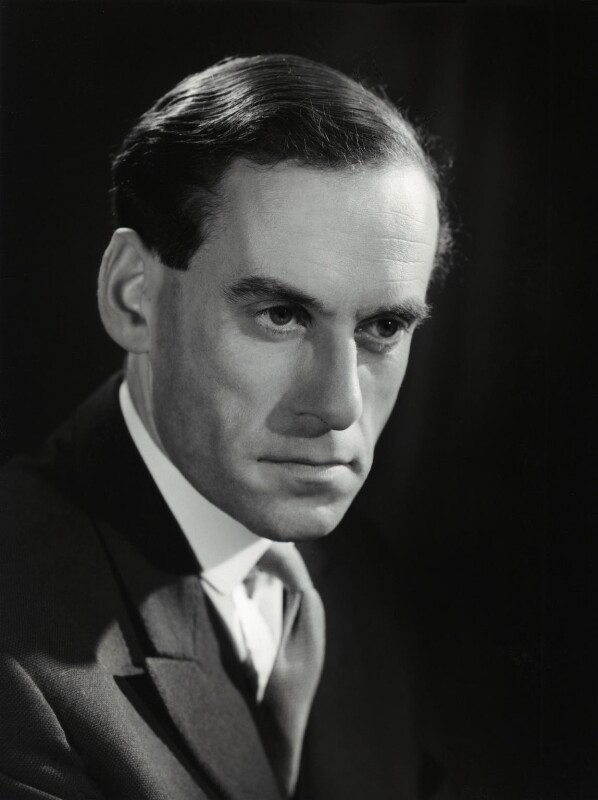

Paddy Ashdown © European Communities, 2005 / EC, Photo: Christian LambiottePaddy Ashdown brought one massive attribute to his ten year role at the head of the Liberal Democrats: he was by personality and character a natural leader, and, whatever faults he had and whatever mistakes he made, that quality of leadership was always recognised. In addition he had an unusual characteristic rare in a politician and particularly in a party leader: he never harboured grudges. However much one disagreed with Paddy he never regarded criticism as disloyalty, indeed he was puzzled when a colleague with whom he had disagreed vehemently was worried about approaching him afterwards. I battled with him in and out of parliament but we remained warm friends to the end. Moreover he enjoyed debate; as such, he had an instinctive Liberal belief in pluralism. Finally, although his image was of a tough military leader with the craggy jaw and the narrowing eyes, he was actually a deeply emotional and sensitive man.

Paddy Ashdown © European Communities, 2005 / EC, Photo: Christian LambiottePaddy Ashdown brought one massive attribute to his ten year role at the head of the Liberal Democrats: he was by personality and character a natural leader, and, whatever faults he had and whatever mistakes he made, that quality of leadership was always recognised. In addition he had an unusual characteristic rare in a politician and particularly in a party leader: he never harboured grudges. However much one disagreed with Paddy he never regarded criticism as disloyalty, indeed he was puzzled when a colleague with whom he had disagreed vehemently was worried about approaching him afterwards. I battled with him in and out of parliament but we remained warm friends to the end. Moreover he enjoyed debate; as such, he had an instinctive Liberal belief in pluralism. Finally, although his image was of a tough military leader with the craggy jaw and the narrowing eyes, he was actually a deeply emotional and sensitive man.

On the face of it Paddy, from his background as a marine and then a diplomat, was a most unlikely Liberal recruit but he loved to tell - often - how in early 1974, when toiling in his Somerset garden, he was approached by the archetypal orange anorak wearing Liberal canvasser. After first giving him the brush off he then invited the persistent canvasser inside. Two hours later Paddy realised that he had always been a Liberal. As with so many of us, that realisation was a fatal error, condemning us to a lifetime of sacrificial commitment to the Liberal cause. So it was with Paddy. Towards the end of 1975, at the age of 35 and with no job to go to in England, he resigned from the Foreign Office to, as he put it, 'go into politics'.1 A year later he was adopted as the prospective Liberal candidate for what had become his home constituency of Yeovil and this became his key priority, despite the considerable difficulties of securing employment compatible with his new political role.

Paddy was later prone to state that Yeovil was a hopeless seat for the Liberals when he took it on. This was somewhat of an exaggeration. Certainly it had been Conservative since it had been gained from the Liberals at a late 1911 by-election but the long serving local Liberal candidate, Dr Geoffrey Taylor, had squeezed ahead of Labour into a very respectable second place at the February 1974 election and was a bare 32 votes behind Labour in the October election that year. When Paddy became the candidate he believed it would take three elections to win the seat but such was the drive he brought to the task, and his ability to recruit capable workers, plus adopting the strategy of concentrating on local elections, that, unlike almost all other Liberal candidates, he increased the Liberal vote at the 1979 election and climbed into second place. Then four years later, adding the tactical vote squeeze on Labour, he took the seat with an overall majority.

Paddy did not find parliamentary procedure particularly congenial, not least having to speak in the chamber with opponents in front and behind. He was very driven and, as Alan Beith's deputy whip, my one problem was that Paddy accepted too many outside speaking engagements that regularly took him away from parliament and ensured that he would typically come rushing into the chamber or to party meetings at the last minute or disappear early after or even during meetings. Paddy was an excellent member of the parliamentary party. He was always convivial though from a very different background to the rest of us. Possessing remarkable language skills, on one occasion after a late parliamentary session, some of us went for a Chinese takeaway at a nearby café and Paddy showed off by ordering in Mandarin. I teased him suggesting that he had actually phoned up earlier giving the numbers of the dishes on the menu. He was not best pleased!

Like all the five new Liberal MPs who arrived bright eyed and bushy tailed, he was appalled that at the first parliamentary party meeting Cyril Smith and David Alton proceeded to attack David Steel 'viciously' for what seemed to be relatively trivial aspects of the election campaign.2 Then, despite the huge logistical problems of the need to cover the entire parliamentary agenda with only seventeen MPs, both of them, opted out of any participation in the team, refusing to take on spokesmanships.

When adopted as the Yeovil candidate Paddy had decided not to play any role in the party nationally. But he was unable to resist taking a key role in the defence debate at the 1981 Liberal Party Assembly in Llandudno, leading the opposition to the deployment of cruise missiles and thus incurring the wrath of the leadership and endearing himself to the party's radicals. This differential reception was to be reversed at the 1986 assembly at which he did a U-turn on the issue in the seminal defence debate that was damagingly mishandled by David Steel.3 Paddy had never been a unilateralist on defence but this policy reversal was unexpected and, inevitably, greatly disappointing to his mainly younger supporters. It did not help that, in his own words, 'my Assembly speech ... was one of the worst I have ever made.'4

Throughout Paddy's parliamentary career the health of the Westland helicopter company ran like a silver thread. As the biggest employee in his constituency it could do no other. In 1980, soon after his adoption as the local candidate and when Westland was going through a bad patch, it was learned that the company was about sell helicopters to the tyrannical regime in Chile. Paddy opposed the sale and was the immediate target for attack and criticism from Westland workers and their trade unions. Three years later, at the general election, the Westland workers voted solidly for him and this episode taught him a crucial lesson that should be learned by every MP today in relation to Brexit. He wrote:

The dangers of putting your conscience and judgement before your popularity are often far less than we politicians realise. The loss of votes in the short term is often compensated for in the long term by the gain in respect. Many voters want their MPs to do what is right and often respect those who do, even while disagreeing with them. The scope for a bit of courage is far greater than we think it is, even in this age of spin and the dark arts of 'triangulation'.5

Westland raised its head again in 1986 when the passionately pro-Europe Paddy Ashdown nevertheless backed Mrs Thatcher's expensive plan to maintain helicopter production in Yeovil rather than Michael Heseltine's solution of a European consortium under which Westland would become an adjunct producing one part of the aircraft. He preferred to see the Westland workers producing the whole aircraft rather than being 'panel beaters' for pan-European production.

Paddy's decision to avoid involvement in the party nationally brought its problems when he became leader but it also contributed to him being curiously naive about aspects of political 'fixing'. He tended not realise that party leaders, including David Steel, may well use 'extra curricular' tactics to get their way and he found it difficult to accept that sometimes persuasion had to give way to rougher tactics. Paddy's frustration with trying to make a Liberal impact with only seventeen MPs whilst conforming to the parliamentary processes was regularly apparent and, presumably believing that it would give him more freedom to act, he admits to deciding in late 1986 that he would aim to become the next leader of the party6 but those close to him believe that he had made his mind up much earlier.

Paddy retained his Yeovil seat at the 1987 election with a slightly increased majority and there followed all the party machinations that finally led to the merger of the Liberal party and the SDP in January 1988 and the announcement by David Steel the following May that he would not be a candidate for the leadership of the new party. The subsequent leadership election was, in effect, a foregone conclusion. Given a choice between the image of Paddy's personal charisma and the new dispensation he represented and the solid, competent, loyal party servant that was Alan Beith, party members opted for the roller coaster. The final result of 72% to 28% was somewhat unkind to Alan but he acknowledged later that Paddy 'went on to become an absolutely outstanding leader, doing enormous good for the party, earning wide respect, and demonstrating a much firmer commitment to the principles of Liberalism than seemed possible at the beginning.'7

Paddy had the huge task of forging the new party. David Owen opted out - arguably both a blessing and a blow - but Roy Jenkins had supported him from day one of his candidature. Given Paddy's temperament, being able to start from scratch suited him but his lack of knowledge of the Liberal Party, which formed the bulk of the active membership of the new party, led him into early errors. First, he initially believed that economic liberalism had been downplayed in the Liberal Party and wished to rectify this. His first pamphlet, After the Alliance, published soon after the 1987 election8 when it became apparent that a merged party would be formed, certainly trailed some of those views, albeit softened for the members whose support he knew he would soon have to win. The history of the party and its debates demonstrate that this strand, whilst vociferous, had always been a minority and that, particularly since Jo Grimond's leadership, social liberalism had been the dominant force. Fortunately the practical tasks he had to face largely sidelined such longer term issues and his first book as leader concentrated on community and on the individual as citizen and barely touched on economics.9

The second consequence of his lack of involvement with the wider party was the narrowly utilitarian view he took initially of the issue of the new party's name. The issue had riven apart the Merger Negotiating Team in 1987-8810 and each party tried to insist on its name coming first in the title. Paddy was unaware of the significance of the name for Liberals who had been committed to the party for many decades, and thought that the way to resolve the matter was to call the party The Democrats. The produced an immediate furore and, to his credit, he then appreciated the visceral attachment to the name and resolved the matter by announcing a referendum of all the party members and this poll opted for 'Liberal Democrats'11. At the time he wrote:

Being a relative outsider compared to the older MPs, I had, in my rush to create the new party, failed to understand that a political party is about more than plans and priorities and policies and a chromium-plated organisation. It also has a heart and a history and a soul - especially a very old party like the Liberals... I had nearly wrecked the party by becoming too attached to my own vision and ignoring the fact that political parties are, at root, human organisations and not machines.12

Although it was not particularly apparent, Paddy initially struggled with the responsibility of performing in the Commons chamber, particularly with the gladiatorial contest of Prime Minister's Questions. In any case the early days of his leadership were basically a rescue operation. The joint Liberal/SDP vote at the 1987 general election was 23% but the poll ratings of the new party steadily declined over the next two years to a low of 5% in October 1989.13 The European Parliament elections of 12 June 1989 were Paddy's first national electoral test as leader. They were a disaster, with the Green Party leapfrogging the party to take third place, polling more than twice the new party's tally: 14.5% to 5.9%. The scale of the Green party's surge was a considerable surprise and Paddy described it as the lowest point of his leadership and he commented that he went to bed on election night 'tormented by the thought that the party that had started with Gladstone would end with Ashdown.'14 It says a great deal for his doggedness that outwardly he showed little sign of his worries and he carried on as if it was a minor hiccup. It would be another eight months before the polls began to move in the party's favour.

He had immediately found a Liberal cause to espouse and expound. On 4th and 5th June 1989, just before the European election, the massacres in Tiananmen Square, Beijing, had taken place. Paddy quickly got involved and, together with Bob Maclennan, flew out to Hong Kong whose citizens were understandably now worried about their future when the colony was handed back to China in 1997. On his return he persuaded the party to adopt the thoroughly Liberal policy of guaranteeing the Hong Kong Chinese the right of abode in the United Kingdom if things turned nasty for them after 1997 - a right that had been taken away by the Conservative government, supported opportunistically by a Labour opposition fearful of losing votes. The prospect of 3.5 million Chinese arriving from Hong Kong was certainly unpopular amongst the electorate but it was morally right and a distinctive stance by the party.

As ever, politics in 1989 and 1990 followed Harold Macmillan's adage that it is events that determine politics15 and just as Hong Kong had provided a distinctive issue, the IRA's murder at the end of 1990 of Ian Gow, the Conservative MP for Eastbourne, and Mrs Thatcher's key aide, caused a problematic by-election. Paddy's initial response, together with other national leaders, was not to fight a by-election in such circumstances, but Chris Rennard, the party's Director of Campaigns, persuaded Paddy that the seat could be won. Rennard was right and the Liberal Democrats victory in the by-election in his Eastbourne constituency, followed five months later by a victory in Ribble Valley, pushed the Liberal Democrats' poll figure up to 16%. A further by-election gain in Kincardine and Deeside in one of the last three by-elections before the 1992 general election provided a further boost to the party in the lead up to Paddy's first big national Westminster test. His determination and campaigning across the country over the past three years had borne fruit and the party emerged from the campaign with reasonable success, and plaudits for Paddy's leadership. If the result had been somewhat disappointing to Paddy he was certainly assuaged by successes in the first two by-elections of the new parliament, in Newbury and Christchurch, following a year later by victory in Eastleigh and then Littleborough and Saddleworth, all of which gave a considerable impetus to the party as it headed towards the next general election.

Throughout this early period of his leadership, Paddy pushed the party's local government campaigns, being extremely conscious of the role council victories had played in his own progress in Yeovil. The vote nationally rose from 18% to 26% between 1988 and 2000 and the number of seats won almost doubled and the number of councils controlled increased threefold. By 1996 the party had overtaken the Conservatives in the number of elected councillors.

As with the Liberal Party since 1955, the Liberal Democrat manifesto in 1992 for Paddy's first election expressed the party's firm support for a united Europe. As Prime Minister John Major's problems with his Eurosceptic rebels grew as the 1992 parliament continued to grapple with the Maastricht Treaty, it was the Liberal Democrat's twenty MPs who rescued the government's pro-treaty policy on numerous occasions. Paddy was prepared to bear the brunt of the highly vocal opprobrium from those in and out of parliament for his and his party's principled votes in line with the party's longstanding European stance, even if it meant voting with an increasingly unpopular Conservative government.

On the 9th May, one month after the 1992 general election, at a speech in Chard in his constituency, Paddy carefully calibrated a move away from the previous basic strategy of 'equidistance', ie regarding Labour and Conservative parties as equal opponents and, in effect, by extension, equally potential partners in a coalition or a similar governmental arrangement. Instead he proposed placing the Liberal Democrats firmly on the Left of politics with a predilection to oppose the Conservative government. Though he was deliberately steering the party in a specific direction, he was simply reaffirming Jo Grimond's aim of a 'realignment of the Left' and articulating clearly what most Liberals actually felt. Even so, it was not universally regarded as tactically wise and it was criticised by a swathe of party members, including particularly some in the parliamentary party. Nevertheless the party formally backed its leader's positioning.

No-one in the party could have realised what Paddy had in mind as the practical outworking of his strategy, and indeed it only emerged much later. Following a first social meeting with Tony Blair on 14 July 1993 Paddy began to develop a clandestine political relationship with the future Labour party leader which continued until Blair's Labour government rejected the Jenkins Commission Report on electoral reform in late 1998. Paddy's aim was to establish some form of alliance or arrangement with Labour which would provide sufficient electoral traction to keep the Conservatives out of office virtually permanently. The latter aim was certainly extremely worthy but his means of achieving it betrayed a considerable näiveté about the nature of the Labour party and, indeed, of Blair himself. A rose-tinted view of Labour might well be seductive in Yeovil, with the party polling around 10%, but its control freakery and hegemonic tactics in its northern industrial fiefs showed a very different party. It was the urban Liberal Democrats who were most vocal when the implications of Paddy's efforts to liaise with Blair were seen as threatening the independence of the party finally become known.

It is ironic that Paddy, in his assessment of Tony Blair,16 says that he overestimated 'the power of his most formidable weapon: his charm', when the comment could well be applied to Paddy himself in that he had to believe in his charisma as the means of getting any arrangement with Labour accepted by the Liberal Democrats, unless his remarkably optimistic judgement of his party might prove to be accurate. In any case the only possible circumstance in which any such arrangement was remotely conceivable without proportional representation being guaranteed, would have been a hung parliament with Labour the largest party - a situation impossible actively to work towards. Whether or not Tony Blair was personally genuine in his expressed support for Paddy's 'project' over almost six years is arguable but he certainly could not deliver it. The 'project' was, however, not without its gains. The Robin Cook-Robert Maclennan report on constitutional changes set out a blueprint for devolution, a human rights act, freedom of information legislation, House of Lords reform and modernisation of the House of Commons. A number of these proposals were implemented under subsequent Labour governments. Arguably it also beneficially led to an increased amount of tactical voting at the 1997 general election.

In August 1992, soon after the general election, Paddy flew into Sarajevo and thus took the first step of the engagement with Bosnia which would develop into the most significant and respected aspect of his political life. No other politician had the experience and skills to do what he did for that troubled country. His military background, his people skills, his Liberal principles and his political judgement enabled him eventually to play a highly significant role in establishing a stable future for Bosnia and Herzegovina. In the early days, with war still going on, and flying into the highly vulnerable ancient city of Sarajevo, also no other party leader was as equipped as Paddy was to sleep in tents, to understand how best to avoid snipers and to talk on equal terms with military commanders and diplomats in Sarajevo.

After that first visit he wrote and spoke on the serious situation in Bosnia the imminence of war and of the vulnerability of the Bosnian Muslims to the Serb army and to resurgent Croatian nationalism. No-one took much notice. Thereafter, time after time, he used his one allotted opportunity at Prime Minister's Questions to press the case for intervention in Bosnia, so much so that there were shouts of 'the Honourable Member for Sarajevo' when he rose to speak. Even his Liberal Democrat colleagues were concerned that he was becoming obsessed with Bosnia to the exclusion of domestic issues but in retrospect he was proved right on the lethal situation in Bosnia and the need for intervention, and his perception of the situation and his persistence in drawing attention to it were in the best traditions of Liberal action.

The visits to Bosnia continued, often in extremely dangerous situations, but in early 1993 he took time off to undertake a number of trips around Britain in order to discover first-hand the living and working conditions of the British people. This initiative resulted in his second book, Beyond Westminster17 and good publicity around the country. The 1997 election produced 46 Liberal Democrat MPs - the highest number since 1929 - giving Paddy an enhanced role in the Commons but the slow demise of 'The Project' with Tony Blair, which Paddy took a long time to accept, took the edge of his passion for the need to innovate and he became weary of being in perpetual motion as party leader and began to plan to retire, announcing it January 1999. He followed this by retiring from his Yeovil seat in time for David Laws to be successfully in place before the 2005 election. He became a life peer a month after the 2001 election.

In mid-2001 he was approached by the international community on Tony Blair's initiative to take over as the High Representative for Bosnia and Herzegovina the following May and immediately set about putting together a team to enable him to do the job effectively. Typically, he also set about learning the Serbo-Croat language - now known as Bosnian, Serbian or Croatian depending on which country one is in - describing it as the most difficult of the many languages he had learnt. In effect the job entailed him being a substitute president of the country until sufficient stability was assured to enable a national government to take over. It was acknowledged by just about everyone, apart from the intransigent Serbs, that he did the job superbly for the three years and eight months of his extended mandate. He and Jane fell in love with the country and its people and this was completely reciprocated.

It was an exceptionally difficult job in a broken country ravaged by civil war and with its people having suffered untold hardships and war crimes. It required tough decisions at times and cajoling at others. He did the job in a remarkably Liberal fashion, involving the local people at every level. The tributes from Bosnian leaders following his death were symptomatic of the warmth and respect in which he was held. In a very real way the record of his time in Bosnia and Herzegovina demonstrate what a good prime minister of the UK he would have made.

In January 2007, exactly year after Paddy's return from Bosnia, Gordon Brown took over from Tony Blair as prime minister. There followed a rather curious postscript to The Project. Brown, possibly its most intransigent opponent within the Labour government apart from John Prescott, asked Paddy to join his government as Secretary of State for Northern Ireland. Paddy was adamant that for Liberals to join a majority Labour government would be disastrous for the party. He would be isolated and bound by collective responsibility involving support for a raft of Labour policies, such as those involving civil liberties, to which he and the Liberal Democrats were totally opposed. He turned down the invitation.

Even then political responsibility had not finished with Paddy. Whilst on a long holiday, ending with visiting Jane's relations in Australia, he was phoned by David Miliband, the Foreign Secretary, to ask Paddy to become the UN Special Representative of the Secretary-General in Afghanistan. He said 'no' but was put under considerable international pressure. He replied that he did not wish to do the job but that if there was such a broad international consensus, and he was given the tools to do the job, as an old soldier, he could not refuse. He also stipulated that his appointment would have to be approved by Hamid Karzai, the president of Afghanistan. He was told that everyone was agreed that he was the person for the job. Karzai agreed and reluctantly Paddy took on the massive task that would necessitate him being away for two years with no possibility to take Jane with him given the insecurity and Islamic constraints of Afghanistan. Paddy threw himself into the preparations for the job but suddenly Karzai withdrew his agreement and preparations were precipitately ended, much to Paddy's and the family's annoyance but intense relief.

Paddy was instinctively and emotionally opposed to entering a coalition with the Conservatives in 2010 but reluctantly accepted that it was probably inexorable and was the decision of the parliamentary party, endorsed by a special conference of the party. His final task for the party was to be in charge of the 2015 post-coalition general election campaign. The Liberal Democrats were caught in a pincer movement: no gratitude nor even acknowledgement by the Conservatives of the benefits of Liberal Democrat participation in coalition, and excoriated by Labour for abandoning all the party's traditions and history. It was impossible to persuade the electorate that its oft-repeated refrain on the doorstep that it 'wanted politicians who put country before party' was precisely what the Liberal Democrats had done. The party, despite all the efforts by Paddy and his team, was hammered, losing two thirds of its vote and its MPs dropping from 57 to 8. The biggest blow for Paddy was the loss of his old Yeovil seat.

His end came rapidly. Paddy announced on 2nd November last year that he had been diagnosed with bladder cancer. These days there is much more of an acceptance that cancer is not necessarily the early death sentence that once it was, but Paddy died less than two months later, on 22nd December. It is ironic that having survived all the dangers of the Borneo jungle and the Bosnian war, it was a 'mere' fatal disease that caused his death. The trite comment often used as an attempt to ease the pain of family is that the person would not have wished to survive in a debilitated state but that would definitely have been the case with Paddy. It is impossible to imagine him putting up with the frustrations of a long decline.

Assessing Paddy is a very broad task. He was a brilliant man who was a success at everything he tackled. He was intensely loyal and once he realised that he was a Liberal, thanks to the efforts of the famous though anonymous Liberal canvasser in the anorak way back in January 1974, he never deviated from his commitment to the Liberal cause over the next forty-four years. He was instinctively a Liberal, treating everyone alike with no awareness of 'status', which made him one of the most convivial and generous colleagues one could have. He was a great man for The Plan, bullet points and all, with tasks and targets for each member of the team - and his own work rate inhibited everyone else from complaining. He had a permanent search for the new idea or initiative, however impolitic or unattainable, and, once he had convinced himself it was virtually impossible to disabuse him of its value. His last campaign, for instance, was his 'More United' project of July 2016 aiming to put together a cross-party tactical cooperation group of Liberals and fellow-travellers to facilitate tactical voting. Some of us who had been round this course all too often, criticised him all to no avail. Typically he responded to every email. This trait did not prevent him from changing tack if he decided that it was required. The most serious criticism he faced was linked to this in that he seemed to be prone to be too influenced at times by those who spoke to him last, such as with his U-turn on cruise missiles.

Paddy was a remarkable and improbable mixture of toughness and emotion. His ability to empathise with the victims of violence or of prejudice was manifest but it was coupled with a steely determination to act in accordance with duty and judgement. He developed into a compelling public speaker and his Liberal audiences were very indulgent of his tendency to repeat the same joke or anecdote. He was himself a source of many aphorisms and pithy comments quoted by others. He was a passionate family man who revelled in and relaxed with Jane, with his two children, Kate and Simon, and with his grandchildren. He had an ability, unusual in a politician, to be able to take a short break, often at short notice, and to go off skiing or to the Ashdown cottage in Burgundy. Jane was a great partner and supporter and particularly played an important role with Paddy in Bosnia.

It is a great commendation that everyone who worked for him, whether voluntarily or professionally, loved the man and enjoyed their time with him, even though he drove them extremely hard. One reason why it was so enjoyable was that he was a genuine pluralist who enjoyed debate and discussion and encouraged all his associates to argue with him.

He was a voracious reader and writer who, from 1987, produced a stream of books on Liberalism and on military and associated topics. Paddy recognised the importance of writing and of setting out analysis and ideas and he confessed that he enjoyed doing it. He was the first party leader since Jo Grimond to have produced books and so many pamphlets. His last book, containing riveting biographical essays on individuals who stood up to Hitler, included a very significant comment on our times:

In reading this book you may be struck, as I was in writing it, by the similarities between what happened in the build up to World War II and the age in which we now live. Then as now, nationalism and protectionism were on the rise, and democracies were seen to have failed, people hungered for the government of strong men; those who suffered most from the pain of economic collapse felt alienated and turned towards simplistic solutions and strident voices; public institutions, conventional politics and the old establishments were everywhere mistrusted and disbelieved; compromise was out of fashion; the centre collapsed in favour of the extremes; the normal order of things didn't function; change - even revolution - was more appealing than the status quo, and 'fake news' built around the convincing untruth carried more weight in the public discourse than rational arguments and provable facts. Painting a lie on the side of a bus and driving around the country would have seemed perfectly normal in those days.18

In the same book there was also a comment on the flaws of one of his brave subjects that could never be applied to Paddy himself:

... they were the flaws which can often weaken the soldier who has more intellect than is needed for the job. He was a man of thought rather than of action, who weighed every step so carefully that he could sometimes miss the fleeting opportunity whose lightening exploitation is the true test of the great commander.19

Finally, Paddy summed himself up:

I was a soldier at the end of the golden age of imperial soldiering; a spy at the end of the golden age of spying; a politician while politics was still a calling; and an international peace-builder backed by Western power, before Iraq and Afghanistan drained the West of both influence and morality.20

There is a fine portrait of Paddy in the National Liberal Club. Unlike every other portrait in the club the subject is not in formal dress. Paddy insisted in being painted in an open-neck shirt and rolled up sleeves. Visible around him are three references to the peoples of Bosnia, including a picture of the iconic Mostar bridge. Typical of the man!

1 Paddy Ashdown, A fortunate life, Aurum Press, 2009, p.162.

2 ibid., pp.212/213.

3 Michael Meadowcroft, Eastbourne Revisited, Radical Quarterly 5, Autumn 1987.

4 Ashdown, A fortunate life, pp.224/225.

5 Ibid., p.199.

6 Ibid., p.228.

7 Alan Beith, A view from the North, Northumbria University Press, 2008.

8 Paddy Ashdown, After the Alliance, Liberal Challenge Booklet 10, Hebden Royd Publications, September 1987.

9 Paddy Ashdown, Citizens' Britain - A Radical Agenda for Britain, Fourth Estate, 1989.

10 It was the main issue over which I resigned from the Liberal team on 12 January 1988.

11 Paddy Ashdown, A fortunate life, pp.246/247.

12 ibid., p.246.

13 Poll of polls in Roger Mortimore and Andrew Blick, Butler's Political Facts, Palgrave Macmillan, 2018, p 435. Paddy's oft quoted story that on one occasion the polls could not detect enough Liberal Democrat to provide a figure and therefore registered an asterisk was never true.

14 Paddy Ashdown, A fortunate life, p.248.

15 Cited in Dictionary of Conservative Quotations, ed Iain Dale, Biteback, 2013.

16 Paddy Ashdown, A fortunate life, p.324.

17 Paddy Ashdown, Beyond Westminster, Simon Schuster, 1994.

18 Paddy Ashdown, Nein! Standing up to Hitler 1935-1944, William Collins, 2018.

19 Ibid., p.9.

20 Paddy Ashdown, A fortunate life, p.5.

Michael Alison

Michael Alison Paddy Ashdown

Paddy Ashdown David Austick

David Austick John Arnold Baker

John Arnold Baker Maureen Baker

Maureen Baker Paul Baker

Paul Baker Ray Beaty

Ray Beaty Audrey Bee

Audrey Bee Connell Bee

Connell Bee Dr Maury Benard

Dr Maury Benard Viv Bingham

Viv Bingham Peter Boizot

Peter Boizot Michael Burrell

Michael Burrell Leslie Chapman

Leslie Chapman Donald Chesworth

Donald Chesworth David Chidgey

David Chidgey David Chidgey

David Chidgey Lord Chitnis of Ryedale

Lord Chitnis of Ryedale Maggie Clay

Maggie Clay Stanley Cohen

Stanley Cohen Ken Colyer

Ken Colyer Patrick Crotty

Patrick Crotty George Cunningham

George Cunningham Ralf Dahrendorf

Ralf Dahrendorf Tom Dale

Tom Dale Jack Diamond

Jack Diamond Lord Gryff Evans

Lord Gryff Evans Penny Ewens

Penny Ewens Derek Ezra

Derek Ezra Maurice Faure

Maurice Faure Ronnie Fearn

Ronnie Fearn Ronnie Fearn

Ronnie Fearn Ronnie Fearn

Ronnie Fearn Clement Freud

Clement Freud Jonathan Fryer

Jonathan Fryer Douglas Gabb

Douglas Gabb Tony Greaves

Tony Greaves Tony Greaves, an appreciation

Tony Greaves, an appreciation Jo Grimond: an appreciation

Jo Grimond: an appreciation John Gunnell

John Gunnell Pat Hawes

Pat Hawes Peter Hellyer

Peter Hellyer Richard Hoggart

Richard Hoggart Albert Ingham

Albert Ingham Russell Johnston

Russell Johnston Denis Mason Jones

Denis Mason Jones Nigel Jones

Nigel Jones Trevor Jones

Trevor Jones Trevor Jones

Trevor Jones Dr Graham Kirkland

Dr Graham Kirkland Joseph Kitchen

Joseph Kitchen Peter Knowlson

Peter Knowlson Enid Lakeman

Enid Lakeman Eric Lubbock

Eric Lubbock Robert Maclennan (Lord Maclennan of Rogart)

Robert Maclennan (Lord Maclennan of Rogart) Diana Maddock

Diana Maddock Min Marks

Min Marks Rev Albert McElroy

Rev Albert McElroy Joseph Mellor

Joseph Mellor Lord Merlyn-Rees

Lord Merlyn-Rees Trevor Millington

Trevor Millington Richard Moore

Richard Moore David Morrish

David Morrish David and Joan Morrish

David and Joan Morrish Brooke Nelson

Brooke Nelson Mary Ness

Mary Ness Mike Oborski

Mike Oborski Ed O'Donnell

Ed O'Donnell Jerry Pearlman

Jerry Pearlman Rev Geoff Percival

Rev Geoff Percival Bill Pitt

Bill Pitt Jack Prichard

Jack Prichard Lord Rochester

Lord Rochester Keith Schellenberg

Keith Schellenberg Michael Shaw (Lord Shaw)

Michael Shaw (Lord Shaw) Dr Jeffrey Sherwin

Dr Jeffrey Sherwin David Shutt

David Shutt Sir Cyril Smith

Sir Cyril Smith Trevor Smith

Trevor Smith Peter Sparling

Peter Sparling Michael Steed

Michael Steed Michael Steed

Michael Steed Richard Stokes

Richard Stokes Andrew Stunell

Andrew Stunell Eric Syddique

Eric Syddique Alf Tallant

Alf Tallant Geoff Tordoff

Geoff Tordoff Donald Wade

Donald Wade Joyce Wainwright

Joyce Wainwright Richard Wainwright

Richard Wainwright John G Walker

John G Walker Philip Watkins

Philip Watkins Donald Webster

Donald Webster Peggy White

Peggy White Ray Whitelock

Ray Whitelock Harry Whitham

Harry Whitham Lord Wigoder of Cheetham

Lord Wigoder of Cheetham Margaret Wingfield

Margaret Wingfield Harry Woodhead

Harry Woodhead

The recent sudden death of Paul Baker deprives Leeds political life of a remarkably sage and constantly radical individual. He had a gentle confidence in being able to sense the right "line" on any current issue without giving any hint of arrogance. There are few enough colleagues whose judgement was as reliable and as sound as Paul's, and I shall certainly miss him personally.

The recent sudden death of Paul Baker deprives Leeds political life of a remarkably sage and constantly radical individual. He had a gentle confidence in being able to sense the right "line" on any current issue without giving any hint of arrogance. There are few enough colleagues whose judgement was as reliable and as sound as Paul's, and I shall certainly miss him personally.