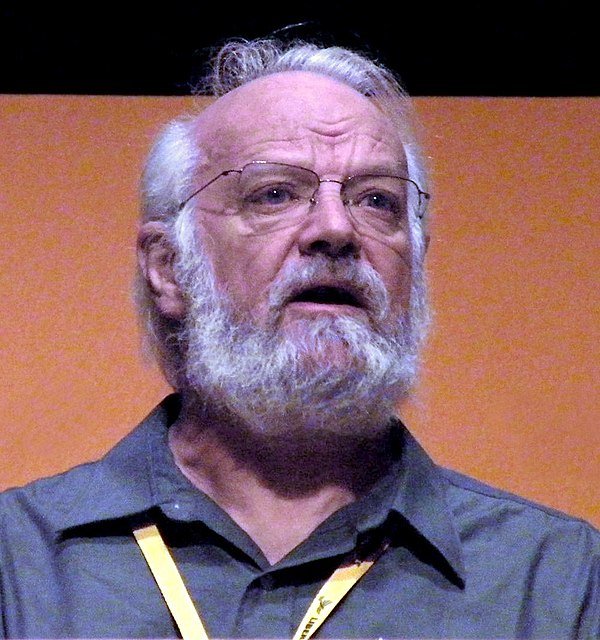

Photo: Keith Edkins, CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons Michael Steed was the epitome of intellectual rigour; this, coupled with a remarkable memory for detail, made him a formidable politician. Fortunately for Liberalism he realised: ‘in my late teens that liberalism, not socialism, must be at the core of a worthwhile and effective radical party’[1] and he never wavered from that view. Michael had three particular strands to his politics, first was his active commitment to the promotion of his Liberal values, particularly international Liberalism, second, and more academic, was the development of psephology - the study of electoral processes - in which he was acknowledged to be one of the leading specialists; and third was a deep interest in Liberal history. Two of his specific campaigns were for gay rights and for European integration, but it was his awareness of the instinctive Liberal understanding of the human personality and its need for freedom, coupled with a deep distaste for Tory imperialism, the aggressiveness of the Tory right, and an awareness that on the issue of European integration, ‘Labour was easily the most reactionary and protectionist party’, that confirmed his commitment to Liberalism.[2]

Photo: Keith Edkins, CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons Michael Steed was the epitome of intellectual rigour; this, coupled with a remarkable memory for detail, made him a formidable politician. Fortunately for Liberalism he realised: ‘in my late teens that liberalism, not socialism, must be at the core of a worthwhile and effective radical party’[1] and he never wavered from that view. Michael had three particular strands to his politics, first was his active commitment to the promotion of his Liberal values, particularly international Liberalism, second, and more academic, was the development of psephology - the study of electoral processes - in which he was acknowledged to be one of the leading specialists; and third was a deep interest in Liberal history. Two of his specific campaigns were for gay rights and for European integration, but it was his awareness of the instinctive Liberal understanding of the human personality and its need for freedom, coupled with a deep distaste for Tory imperialism, the aggressiveness of the Tory right, and an awareness that on the issue of European integration, ‘Labour was easily the most reactionary and protectionist party’, that confirmed his commitment to Liberalism.[2]

Born on 25th January 1940 into a nominally Conservative family he discovered his political affinity for himself rather than inheriting it and somewhat precociously, and bravely, he derived his initial appreciation of liberalism by reading John Morley’s two volume biography of Gladstone. Even more precociously he re-founded the local Liberal association whilst still at school. Happily this coincided with Jo Grimond becoming the Liberal party leader and Steed found Grimond’s brand of left radicalism congenial. He admitted to going through a brief socialist phase ‘ as part of growing up but became convinced that liberalism had to be at the heart of progressive and radical politics .[3]

He won a scholarship to Corpus Christi College, Cambridge, and began by reading economics but switched to geography, which was particularly apposite for his later analyses of voting trends. It was whilst that he got involved in national politics having found himself on a delegation to a seminar run by the World Federation of Liberal and Radical Youth. In the time-honoured way of Liberal Party politics this quickly led to him becoming the national chair of the Union of Liberal Students with an ex-officio seat on the party’s National Executive and on the Liberal Party Council. He rapidly became involved in the radical causes that remained with him - and the Liberal party - thereafter: constitutional reform, European federalism, regional devolution, electoral reform, homosexual equality and anti-apartheid. It was whilst trying to deliver aid to the victims of the 1960 Sharpeville massacre that he was refused entry into South Africa by the regime.

Steed was an officer of the National League of Young Liberals during much of the rise of the radical Young Liberal movement - nicknamed the Red Guard by sections of the press - but he avoided the radical action that enveloped the party in public controversy. His contribution to a Liberal Democrat History Group meeting on this period gave no hint of any personal involvment with the Young Liberals involvement in direct action, often in conjunction with other left groups, over the Vietnam war, South African apartheid and Rhodesia’s white government’s Unilateral Declaration of Independence, plus arguing for UK withdrawal from NATO and other targets of a newly radicalised youth culture. [4] On the other side those broadly defined as the party establishment were outraged at what they saw as vote losing actions at odds with party policy and the parliamentary process. The highly public divisions within the party came to a head at the 1965 Liberal Assembly in Scarborough and dragged on thereafter until, in December 1970, following the disastrous results at that year’s general election, the party leader, Jeremy Thorpe, set up a committee under the chairmanship of Stephen Terrell QC, the party’s candidate in Eastbourne, to examine the existing relations between the Young Liberal movement and other sections of the Liberal party, to take evidence and to make recommendations. Its report’s main recommendation was that membership of the party should only be through a constituency party.[5] One of Steed’s criticisms of the report was that it was addressed to the party leader, Jeremy Thorpe, rather than to the party. He made a similar point in a speech at the time, saying that the party must shift attention away from personalities to a wide-ranging debate about ideology, principles and policies. [6]

Michael Steed leaflet 1967Even though Michael Steed was the Chair of the University Liberal Students during much of this time he was conspicuously absent from what were seen as its excesses and did not contribute to either of the two seminal Young Liberal publications of the period.[7] In essence he was in the movement but not of it. With his more academic and analytical mind, and being somewhat older than the key leaders of the movement, the party’s slightly scurrilous magazine, Radical Bulletin,[8] dubbed him the venerable Steed . He commented on the period at a Liberal Democrat History Group seminar in 2010.[9] However, when the Young Liberals were determined to test their policies and tactics out with the electorate, and were the prime movers of the party contesting the Brierley Hill by-election on 24 April 1967, Steed was the obvious choice as candidate. It was a quixotic campaign in a constituency that had not been fought by Liberals since 1950 and which, in fact, was not contested in the following 1970 election. He polled just 7.8% and forfeited his deposit.

Michael Steed leaflet 1967Even though Michael Steed was the Chair of the University Liberal Students during much of this time he was conspicuously absent from what were seen as its excesses and did not contribute to either of the two seminal Young Liberal publications of the period.[7] In essence he was in the movement but not of it. With his more academic and analytical mind, and being somewhat older than the key leaders of the movement, the party’s slightly scurrilous magazine, Radical Bulletin,[8] dubbed him the venerable Steed . He commented on the period at a Liberal Democrat History Group seminar in 2010.[9] However, when the Young Liberals were determined to test their policies and tactics out with the electorate, and were the prime movers of the party contesting the Brierley Hill by-election on 24 April 1967, Steed was the obvious choice as candidate. It was a quixotic campaign in a constituency that had not been fought by Liberals since 1950 and which, in fact, was not contested in the following 1970 election. He polled just 7.8% and forfeited his deposit.

During this period he had been a student of David Butler at Nuffield College, Oxford, but his rapidly increasing commitment to psephological research and analysis led him to abandon his PhD. In 1966 he went from Nuffield to Manchester University as a Lecturer in Government, a post he held until 1987, taking early retirement through ill health. Alongside his commitment to the Liberal party he developed a reputation as an expert and independent commentator on election results. He contributed the statistical analysis to the definitive Nuffield Study on each general election from 1970 to 2005, latterly with John Curtice. He also provided the annual analysis of local elections in The Economist from 1968 to 1991. Steed developed an encyclopaedic knowledge of even the smallest local council election and Vernon Bogdanor recounted that as a graduate student at Nuffield, studying local elections, he (Steed) would scan local newspapaers at breakfast. One morning he exclaimed loudly, “Good heavens!” We asked what disaster had occurred. He replied that an independent had won a local by-election at Newbury and that this had not happened since 1905"![10]

In the course of analysing results he developed a more sophisticated method for calculating the swing between competing parties than that hitherto used by David Butler. The Steed Swing, he argued, coped better with three-party politics than Butler Swing . He also had a deep awareness of electoral geography and, with John Curtice, was able to show that regional identities, coupled with historical influences, differentially affected the national outcomes.

Steed continued to contest elections and he was the Liberal candidate in the more promising Truro constituency at the 1970 general election but finished third. In 1973 he contested the Manchester Exchange by-election, a previously solid Labour seat with little Liberal activity. Steed polled 36.3% and came a creditable second, the Liberals constructing a community politics campaign from scratch, particularly concentrating on soliciting and dealing with electors’ individual problems - a tactic that the successful Labour candidate memorably labelled ‘instant compassion’. He then unsuccessfully fought Manchester Central in the February 1974 general election and Burnley in 1983. He also fought Greater Manchester North at the 1979 European parliament election.

Steed’s difficulty as a parliamentary candidate was not uncommon among academics fighting elections in that his warm personality was at times clouded behind his intellectualism. A very different side to Steed’s personality was in his bravura singing performances at the party’s Glee Club on the last evening of the annual party conference. He also contributed a number of skilful parodies and alternative words to old tunes, many of which are enshrined in the Liberator Songbook.[11]

Steed was a prolific pamphleteer and the contributor of chapters to numerous books but never produced a major book under his own name. It may well have been, similar to his abandonment of his PhD thesis, that confining himself over a long period to a single subject bored him and he preferred to absorb and to utilise a wide range of knowledge.[12] Equally eclectic was his support for a wide range of activism, from international campaigns to regional and local projects. His internationalism, his wide knowledge of European politics and his particular passion for French politics, led him to write a booklet, ‘Who’s a Liberal in Europe?’[13] This was followed by the chapter, ‘The Liberal parties in Italy, France, Germany and the United Kingdom’ in a 1982 book,[14] and also, in 1988 a chapter, jointly with Patrick Humphrey, ‘Identifying Liberal parties’ in 1988.[15] Steed also took a leading role in the updating of the preamble to the Liberal Party Constitution in 1969. In 1976 he devised the system for electing the leader of the Liberal Party by the party membership rather than only by the MPs. In 1978 Steed was elected as President of the party, defeating Christopher Mayhew, a former Labour MP and a recent convert to the Liberal Party.

In 1970 he married Margareta Holmstedt, a Swedish Liberal who was a lecturer at Bradford University. They set up home in Todmorden the Pennine textile town on the border with Lancashire and thus roughly halfway between their two universities. Whilst living there he was elected to Todmorden Town Council serving from 1987 to 1991. They eventually drifted apart, separating in 1990 and divorcing in 2004. Margareta continued on the council and become its mayor 2010-11.

In 1982 I benefited personally from Steed’s electoral knowledge and his forensic skills. The Boundary Commission’s recommendations for Leeds had produced an unwinnable home constituency which partnered two strong Liberal wards with two very different wards which, though contiguous on the map, had only become part of Leeds at the local government reorganisation of 1974. The problem for the reviewers was that Leeds had eight constituencies but thirty-three wards. Understandably the Boundary Commission sought to combine five of the smaller wards in to a constituency as opposed to communities of interest. The Leeds Liberals made a submission opposing the proposals and Steed came to Leeds to present the case before the Inspector. He was formidable with a vast knowledge of the law and of precedents. In particular he pointed out that it was not obligatory to constrict all the wards within one local authority and that the Tyne Bridge constituency in the north-east bridged two local authorities. He therefore proposed that the outlying ward of Rothwell on the southern edge of Leeds could be included in a Wakefield constituency. The Commission was persuaded by him and the revised proposals produced the Leeds West constituency which the Liberal Party duly won in 1983. In 1983 Steed contributed the chapter on ‘The Electoral Strategy of the Liberal Party’ to a book on many aspects of the party.[16]

The Alliance with the SDP from 1981 and the merger with that party in 1988 put Steed at odds with many of his Social Liberal colleagues. Whereas most of those colleagues opposed the links with the SDP, he took a different view and though he had reservations, he wrote:

I was one of those who did not find the actual transition from Liberal Party to Liberal Democrats easy; the merger process was made avoidably painful. But as a Grimondite Liberal, I never had any doubt as to the principle of merger with the SDP. I am a Liberal Democrat today in the hope of some further realignment.[17]

In 1996 Steed contributed a chapter on ‘The Liberal Tradition’ to a book of essays. In the course of just twenty pages he sets out a brilliant and succinct essay on the essence of Liberalism.[18]

In 1987 Steed he began to suffer a devastating neurological condition the physical effects of which severely curtailed his activities. The condition proved difficult to diagnose accurately. The illness ebbed and flowed and at times it seemed as if it would be imminently terminal. His mental faculties were unaffected and he remained as effective as ever and, In fact, he continued with many writing and speaking engagements, even though he was for many years confined to a wheelchair. He was commenting on Liberal history matters up to a matter of days before his death. Following his forced retirement from his Manchester lectureship, and finding it increasingly difficult to cope with steep hills of the Todmorden area, he returned to his native Kent and became active with the Canterbury Liberal Democrats. He was elected to the Canterbury City Council for a single term in 2008.

In 1999 he met Barry Clements, a master carpenter, at a men’s social meeting in Whitstable and they became long term partners and were formally joined in a civil partnership in 2023. With Barry’s solid and constant help they were able to spend time most years in the South of France. Barry survives him, as do his four sisters and his brother to all of whom he was very close. He died on 3 September 2023.

References

1. Why I am a Liberal Democrat, ed Duncan Brack, Liberal Democrat Publications, 1996.

4. Red Guard versus Old Guard? The influence of the Young Liberal movement on the Liberal Party in the 1960s and 1970s, Report by Graham Lippiatt on a Liberal Democrat History Group meeting on 12 March 2012. Journal of Liberal History 68, Autumn 2010.

5. Report of the Liberal Commission to the Right Honourable Jeremy Thorpe MP (Chair Stephen Terrell QC), 1st July 1971.

6. The Guardian, 15 September 1969.

7. Blackpool Essays - towards a radical view of society, ed Tony Greaves, Gunfire Publications for the National League of Young Liberals, 1967, and Scarborough Perspectives, ed Bernard Greaves, National League of Young Liberals, 1971.

8. Radical Bulletin is still published as an insert within the fifty year plus long running magazine Liberator.

9. Journal of Liberal History 68, Autumn 2010.

10. Obituary, The Times, 16 September 2023.

11. Liberator Songbook, editions 1 to 25, Liberator Magazine, https://liberatormagazine.org.uk/

12. For a list of Steed s publications, see his Wikipedia entry, (accessed 3 January 2024); A list of his contributions to the Journal of Liberal History can be accessed via the Journal s website: https://liberalhistory.org.uk/people/michael-steed/

13. North West Community Newspapers, Manchester, 1975.

14. Moderates and Conservatives in Western Europe, ed R Morgan and S Silvestri, Heinemann Education, 1982.

15. Liberal Parties in Western Europe, ed Emil J Kirchener, Cambridge University Press 1988.

16. Liberal Party Politics, ed Vernon Bogdanor, Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1983.

17. Why I am a Liberal Democrat, ed Duncan Brack, Liberal Democrat Publications 1996.

18. The Liberal Democrats, ed D N MacIver, Prentice Hall/Wheatsheaf, 1996.