for Liberal History Journal

by Michael Meadowcroft

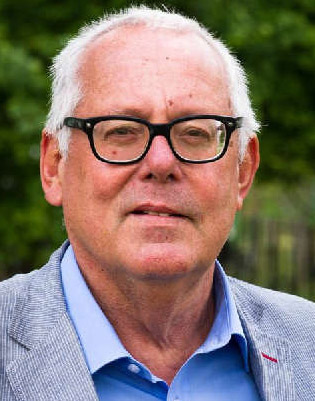

Official portrait of Lord Greaves Photo: Roger Harris, CC BY 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons Tony Greaves never seemed to age. He had a firm belief that politics was capable of transforming society, and his consistent advocacy of local campaigning, community politics and the necessity for both to be anchored in a radical Liberalism had hardly changed from his Young Liberal days. His election to the Lancashire County Council, in 1973, disqualified him legally from his job teaching geography and from then on to his sudden death almost fifty years later he became one of that committed band of Liberals who put the cause before comfort and struggled to find a succession of jobs that would enable him to keep politics as his first priority.

Official portrait of Lord Greaves Photo: Roger Harris, CC BY 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons Tony Greaves never seemed to age. He had a firm belief that politics was capable of transforming society, and his consistent advocacy of local campaigning, community politics and the necessity for both to be anchored in a radical Liberalism had hardly changed from his Young Liberal days. His election to the Lancashire County Council, in 1973, disqualified him legally from his job teaching geography and from then on to his sudden death almost fifty years later he became one of that committed band of Liberals who put the cause before comfort and struggled to find a succession of jobs that would enable him to keep politics as his first priority.

His life before politics captured him was that of a scholarship boy separated from his background by intelligence and an ability to pass exams. Born in Bradford into a family with no direct political involvement, he passed the extremely competitive examination for the direct-grant Bradford Grammar School, but an employment move by his police driving-instructor father took him instead to Queen Elizabeth Grammar School in Wakefield. His successes at ‘O’, ‘A’ and ‘S’ levels enabled him to go to Hertford College, Oxford, and to gain a BA in geography. He followed this with a Diploma in Economic Development at Manchester University. By this time, he had discovered a passion for politics and particularly for political debate. By personality – and influenced by the non-statist radicalism of the then party leader, Jo Grimond – Greaves naturally gravitated to the Liberal cause. He never varied from this commitment except that he soon realised that it was necessary to link theory to activism and to local campaigning. His student Liberal and Young Liberal years were taken up by the burgeoning debates on radical issues of the day, and he was a founding force in the ‘Red Guards’ revival of the Young Liberals in the later 1960s. They became a force at the annual party assembly; in Brighton in 1966, they voted for the party’s commitment to NATO to be referred back and came within one vote of committing the party to putting the nationalised industries under worker control. At a quarterly party council meeting the following year, they were instrumental in committing the party to supporting political asylum in the UK for US citizens leaving their country to avoid being drafted to serve in the Vietnam War and to committing the party itself to aiding such asylum seekers. At this time, 1965–68, he was also agent for Geoff Tordoff in the Knutsford constituency. The Young Liberals were also prominent in the ‘Stop the Seventy Tour’ campaign of direct action to prevent the apartheid South African cricket team touring England in 1970.

In 1968 he married Heather Baxter, a schoolteacher and herself a committed Liberal who became a long-term councillor on the Barrowford Urban District Council and the Pendle Borough Council. Never previously a domesticated ‘new man’, with the birth of their daughters, Victoria (1978) and Helen (1982), Greaves moved from being baffled by others’ attachment to children to being a doting and committed father including looking after daughter Victoria when Heather returned to teaching. Later, he became an even more smitten grandfather with the birth of Robin in January 2019. Typical of Tony was to start a second-hand bookshop in 1993, specialising in Liberal history, from his home and then, after five years, to let it drift, though he still carried on some book-selling until the week before he died. It was also typical that he remained a lifelong supporter of Bradford Park Avenue Football Club despite it playing way down in the sixth tier of English football. He returned to regular attendances at Park Avenue in 2008, even becoming a season ticket holder shortly afterwards.

Despite being an exceptionally transparent individual, he was regularly misunderstood and misinterpreted by political opponents within and without the Liberal Party and the Liberal Democrats. He was a dogged adherent to principle rather than a malevolent opponent on any personal grounds. Attempts to pull rank on him, as Jeremy Thorpe attempted to do in 1970 as party leader over the Young Liberals’ public policy on Palestinian rights, were always going to be met by intransigence, whereas he was always amenable to discussing ways and means of finding acceptable solutions.

In 1981 with a by-election in Croydon North West imminent, the then Liberal leader, David Steel, tried to bounce the party into replacing the adopted Liberal candidate, Bill Pitt, with the SDP president, Shirley Williams. The party took the lack of any consultation badly and responded by backing Pitt, who subsequently won the by-election. Thirty years later this still rankled with David Steel, who drew attention to it in his chapter in a book of essays in honour of Shirley Williams.1 At the time of its publication I consulted Tony Greaves as to whether he agreed that, had David Steel come to party officers and put the case for Shirley Williams standing, we could have delivered the party. He replied, ‘Of course.’

Tony also acted as conciliator at the Liberal Assembly in Southport in 1978. The long-term leader, Jeremy Thorpe, was the subject of hugely embarrassing press stories about his alleged homosexual relationship with Norman Scott and the alleged plot to murder Scott – of which he was subsequently acquitted in court. The party eventually succeeded in persuading Thorpe to resign and obtained an undertaking, which he subsequently broke, that he would not attend the party assembly. At the assembly, Dr James Walsh, Liberal candidate for Hove, tabled a motion censoring the party officers for their treatment of the party leader. The three key party officers at the time, Gruffydd Evans, party president,2 Geoff Tordoff, party chair,3 and myself as chair of the Assembly Committee, decided to take the motion head on and to tell the delegates what party officers had not been able to divulge of Thorpe’s behaviour in recent years. If the motion were carried all three of us would resign. Tony Greaves and a Radical Bulletin colleague, John Smithson, unaware that the trio wanted to force a vote, headed it off by successfully canvassing delegates to have the motion withdrawn.

Tony Greaves wrote a great deal but invariably it was either practical campaigning guides or short pithy commentaries on current political issues or on Liberal Democrat failings. Typically, his six entries in the British Library catalogue are all campaign guides for local elections.4 He was temperamentally more suited to being a skilful editor and an amenable and constructive joint author than the long haul of being a sole drafter of more formidable philosophical pieces. His long series of Liberal News short sharp commentaries would make a study in themselves. His views remained consistent throughout his long political career but he tended to become bored with a task that took too long. Opponents often believed that he was tough and thick-skinned, but this was a style he affected, usually when exasperated with them, and was a misjudgement of his real self, which was warm and sympathetic. I recall that Tony wrote to Jeremy Thorpe criticising his leader’s speech at the 1970 party assembly, just a couple of months after the death of Caroline, Jeremy’s wife, in a road accident. Tony showed me Jeremy’s reply which had upset him: he thanked Tony for his comments and then wrote, ‘there were times this year when I wondered whether there would be any speech.’

His first significant foray into publishing was his editorship of the Young Liberals’ Blackpool Essays produced for the party assembly of 1967.5 Tony’s introduction contains a typicallyforthright statement: ‘The Executives of NLYL6 and ULS7 meeting together informally … seemed to agree that the party lacked a political direction. It was, we arrogantly felt, our job to give it that direction.’ The rest of his introduction is much more self-effacing than he would become. He would not in later years have presented a publication with the comment, ‘Here, then, are the essays. Lambs to the slaughter.’

His next strategic initiative was more significant. Following the disastrous general election in June 1970, at which well over half the Liberal candidates lost their deposits and only six MPs were elected, Tony Greaves worked with Gordon Lishman to present the party assembly in Eastbourne, three months later, with a wholly new party strategy. In what became known as the ‘community politics amendment’, Greaves argued for a ‘dual approach’, working within and without parliament, empowering communities to take initiatives themselves, particularly on local issues, rather than waiting for their elected representatives to take action. It was a strategy that put the Young Liberals’ radical thinking into a political framework and also built on the early signs of Liberal success at local elections.

Accompanying the strategy was a programme of delivering local leaflets urging action and reporting on action taken. Despite the fact that the strategy was not to replace a parliamentary focus but to add to it, it was strenuously opposed by establishment figures in the party. Despite this opposition, the amendment was carried by 348 votes to 236.8 The strategy was taken up enthusiastically by younger and by urban Liberals and led to the burgeoning of the party’s local government base. Ironically, the dramatic increase in the party’s national vote, and its revival at the February 1974 general election, came more from a succession of five parliamentary by-election gains.

Greaves fought his local Nelson & Colne constituency at the two elections in 1974. His three years on the district council, and being elected for the larger county division the year before, produced a respectable vote share of 23 per cent in the February general election but this slumped to 12.4 per cent and a lost deposit in October (the vote needed to retain a candidate’s deposit was then 12.5 per cent). Fast forwarding to his only other local parliamentary contest, in 1997 in the redrawn Pendle constituency, and following sixteen years of highly successful Liberal and Liberal Democrat local government successes and considerable personal popularity, he still only polled 11.6 per cent. It was another salutary lesson – in common with most other cities, and even more marked in the three most recent general elections – that community politics on its own did not produce a sufficiently entrenched core Liberal vote to bring wider success.

After his enthusiasm for Jo Grimond’s leadership and in particular Grimond’s openness to ideas, he was disappointed with his very different successor, Jeremy Thorpe, who believed that it was necessary to be an autocratic leader and, therefore, to try to end the Young Liberals’ radical influence, which he found personally embarrassing. Greaves has stated that ‘Thorpe was a hopeless leader with no philosophical depth of any kind. … He thought he was an organisation man but his efforts there flopped too.’9

In 1976, after Jeremy Thorpe had been persuaded to resign the party leadership, Greaves – perversely, many thought, given his commitment to campaigning and activism – backed David Steel rather than John Pardoe, stating that ‘At first he thought Steel was a “man of the future”, Grimond-style Liberal.’10 But fairly soon he came to change his judgement, not least through Steel’s Lib-Lab Pact initiative in 1977. Greaves believed that, in keeping with Steel’s own perceptions of politics, it was ‘too Westminster’ and ‘was not translated into an effective ground-strategy’.11 He also commented, ‘There was nothing in it for the party. I am not against coalitions. For example, I am a great fan of the current, very successful coalition inScotland, but in the Lib–Lab Pact we gave everything and got nothing.’12 Greaves’ opposition to Steel’s leadership grew steadily over its course, as Steel increasingly demonstrated his disdain for the party organisation and his predilection for running the party by diktat rather than by cooperation;13 and it eventually led to his call for Steel’s resignation when he bounced the party into immediate moves to merge with the SDP following the 1987 general election.14

Greaves was a consistent advocate for community-based campaigning throughout his political life. He wrote a somewhat romanticised chapter on how he saw it being applied in Pendle.15 Sometimes he was too forgiving of the later distortion of the principle into the incessant delivery of the ubiquitous Focus leaflet, which all too often boasted of the Liberal and Liberal Democrat councillors’ successes rather than providing communities with the ammunition to achieve their own successes. Allied to his visceral commitment to local campaigning was his complete absence of pomposity. Even after his appointment to the House of Lords on Charles Kennedy’s nomination in May 2000, he was just as happy to be at a Pendle Borough Council meeting as he was annoying the lordships on the red benches. He remained as loyal and supportive as ever of his long-term Liberal colleagues, but the one change over the years was that his exasperation threshold grew lower with those he felt were wasting his time.

After four years surviving on council allowances and short-term agents’ jobs, he took on a key role as the newly created, and Rowntree Reform Trust funded, organising secretary for the Association of Liberal Councillors (ALC) from 1977 to 1985. A particular attraction of the job was that he could avoid being based at party headquarters in London, setting up a new office in the Birchcliffe Centre, a converted Baptist chapel in Hebden Bridge. Such was his success that, by the time he moved on in 1985, the staff had expanded from Greaves on his own to seven, and the number of Liberal councillors on principal authorities had grown from 750 to 2,500. It was his political skills, organisational drive and ability to produce effective practical guides that underpinned the successes. Following his eight years running ALC, Greaves remained at the Birchcliffe Centre to manage Hebden Royd Publications, which ran the national party’s publishing and marketing operation until the new post-merger party relocated it back to London. After this, Greaves survived by a series of agent and political organiser jobs, plus his bookseller role referred to above.

Greaves’ time with ALC and with party publications spanned the whole fraught period of the Alliance with the SDP and the subsequent merger. His views at the time of the launch of the SDP, as set out in a highly analytical article,16 were a mixture of principle and pragmatism. He deplored the need for the creation of the SDP which he ascribed to the failure of Liberals adequately to define and promote radical Liberal values, particularly as he identified the policy positions of the SDP as to the right of the Liberal Party. He was not entirely negative on the potential for an alliance but went on to oppose an electoral pact that involved giving away swathes of Liberal-fought seats. At the 1983 general election it was noted that:

in a move which, after the election, was to lead to David Steel to call for his resignation, Tony Greaves of the Association of Liberal Councillors had already circulated to Liberal candidates a line-by-line briefing on the differences between the manifesto and Liberal policy designed to demonstrate how the SDP had watered it down.17

This ‘sabotage’, according to Steel,18 was tacitly acknowledged by the authors of the definitive history of the SDP: ‘leading ALC people – people like Tony Greaves and Michael Meadowcroft – saw themselves as being as distant from social democracy as from conservatism.’19 Greaves related later that the Alliance was initially stimulating and broughtmany more council seats but soon proved to be debilitating.20 In particular he stated, ‘it resulted in the intellectual energies on the Liberal side being devoted to promoting Liberal policy to the SDP and defending it (often against what we thought was a more right-wing or more centralising view from our SDP oppos.)’ He went on:

Worse was to follow. The existential crisis that really did follow the merger, combined with a widespread view that the new party should not be plagued by the ‘old’ Liberal versus SDP arguments which had wasted too much energy for too long, meant that discussing policy in the new party was like treading on eggshells. The previously agreed, the non-controversial, and the blandest non-value-laden stuff was the order of the day.21

Immediately following the 1987 general election Greaves, jointly with Gordon Lishman, produced a comprehensive paper on the brief history of the SDP and the Alliance, the nature of liberalism and social democracy, coupled with an appeal to all those in the Liberal Party who were inevitably going to be drawn into the maelstrom of a debate on the existence of their party and the future of liberalism.22 Their appeal was not heeded and the party voted massively for what Greaves clearly saw as the chimera of an easy route to electoral success.

When, following the disappointing set-back at the 1987 general election, David Steel pushed the parties into an early merger, Greaves was one of eight Liberals elected to the Liberal negotiating team in addition to the ex-officio members. Together with Rachael Pitchford, the chair of the Young Liberals, he produced a blow-by-blow account of the five months he and I spent closeted together with a number of like-minded colleagues in the vain endeavour to produce a merger document that would keep the Liberal Party together.23 I have written a short note on Tony’s role in the negotiations;24 suffice to say that Tony was one of the four members who resigned from the negotiating team, unable to accept the final report.25 He spoke against the pro-merger motion at the special Liberal Assembly in Blackpool in January 1988 but, despite his warnings, it was carried on a wave of emotion. His final judgement on the merger was ‘Merger has failed to achieve something better. The new party is universally labelled a “centre party” in a way the Liberal Party never was.’26 His lasting contribution to the new party is the preamble to its constitution, produced – as a third version – by him and Shirley Williams under great time constraints towards the end of the negotiation process and which has survived largely intact.27

Greaves’ personal position in the Liberal Democrats was succinctly summed up in his contribution to a 1996 book of testimonies:28

Fundamentally I am not a ‘Liberal Democrat’ for fundamentally I don’t know what it means!

Only very rarely is a new political ideology invented. Liberal democracy is a set of ideas underlying kinds of government, but it is not an ideology, and nothing has happened in the past eight years to turn it into one.

But simply in order to survive, the Liberal Democrats need an ideology. Liberalism needs a party. And as a liberal who wishes to take an active and serious part in politics, I too need a party. There is only one choice on offer.

He went on to set out why socialism has now had its chance, why he opposes ‘all the malignant forces of corporatism and the greedy and intolerant right which are growing in strength throughout the world’, and sets out his definition of liberalism. He concludes:

So I do my best to encourage the Liberal Democrats to become truly liberal, and liberals to truly embrace the Party. And I produce Focus leaflets and try to help create a liberal local community. What else can I do?

What has happened to the Liberal Democrats since, particularly in its ongoing problem of establishing a clear, defined philosophic identity, able to withstand the chill winds of illiberalism, can in many respects be a vindication of his predictions. One strand that united many of those who opposed the merger, including Greaves, was an understanding that the Labour Party was not a radical reforming party but an autocratic and hegemonic party. Given his leading and often controversial role in national Liberal politics at this time and henceforth, it is surprising that he never appeared on the BBC’s Question Time and only once, on 3 March 1988, on its Any Questions? programme.

Greaves was an admirer of Paddy Ashdown’s principled and consistent espousal of two unpopular causes: the right of all citizens of Hong Kong to acquire British citizenship if the Chinese Communist Party’s increasing dominance became intolerable; and the need for the UK government to intervene to protect the citizens of Bosnia from the military atrocities and war crimes of the Serbs. Ashdown’s continual questioning of the John Major government on Bosnia led a number of Conservative MPs to refer to him as the Member for Sarajevo. However, in a Journal of Liberal History review,29 Greaves was ‘stunned’ by the revelations on domestic policy in the first volume of Ashdown’s diaries.30 Greaves expresses amazement that Ashdown could conceivably believe that he would be able to carry the party with him if he had succeeded in forging some sort of secret political alliance, or even coalition, with Tony Blair’s Labour Party. He wrote in his review of Ashdown’s attempts to persuade Blair of the need for a Lib-Lab arrangement, ‘The result was that Liberal Democrats loved their leader but, insofar as they sensed his strategy, most wanted none of it.’

In 2000 Charles Kennedy, the then Liberal Democrat leader, had the imaginative idea of nominating Greaves as a life peer. He took to his role in the Lords as if it were an enlarged Pendle Borough Council with broader opportunities to achieve worthwhile policies. He had no qualms as to its undemocratic basis, comparing it to the manifest fact that the Commons was also undemocratic in that it did not represent the results of general elections, plus, of course, arguing for a democratic House of Lords elected by the Single Transferable Vote. In her contribution to Liberator magazine’s tribute to Greaves, fellow peer Liz Barker wrote: ‘We saw Tony arrive, harrumph loudly about the flummery of the place, and then settle down to use the Lords to campaign on the subjects about which he was knowledgeable and passionate.’31 In the same obituary, she wrote that: ‘People expected Tony to be sexist. He wasn’t.’ She may have had in mind an uncharacteristic and insensitive comment by Greaves in defence of fellow Liberal Democrat peer, Chris Rennard, who had been accused by a number of party women of harassment:

Lib Dem peer Tony Greaves … made an astonishing attempt to defend Lord Rennard by describing the complaints as ‘mild sexual advances’ and saying ‘half of the House of Lords’ had probably behaved in a similar way. Lord Greaves wrote on an internal party message board: ‘We don’t know the details of anything that may have happened. But it is hardly an offence for one adult person to make fairly mild sexual advances to another. What matters is whether they are rebuffed.’32

It is interesting to note how often commentators who were not close friends or colleagues of Greaves got him wrong. They tended to see the one side of him – as described by a fellow Liberal Democrat peer, ‘uncompromising, argumentative, curmudgeonly, stubborn’33 – without seeing the other side of him: ‘He was our heart and sinew. I can’t begin to tell you how much we will all miss him.’34 The Daily Telegraph obituarist wrote that he ‘was a thornin the side of party leaders from David Steel to Nick Clegg.’35 It also goes on to state that ‘Paddy Ashdown described one policy session in 1998 with Greaves at full throttle as “probably the worst meeting I have ever attended”.’ In fact the relevant Ashdown diary entry only mentions Greaves in passing and clearly it was David Howarth, the later MP for Cambridge and not a natural firebrand, who was the main protagonist.36 Crewe and King in their history of the SDP describe Greaves as ‘the heaviest cross … the modern Liberal leader has had to bear. … In the SDP team’s eyes, Greaves was the Liberals’ Tony Benn – just as fanatical, just as wild, just as committed to “participatory democracy” of a fundamentally undemocratic kind’.37 If this assessment is correct, it is curious that the SDP team turned to Greaves to work with Shirley Williams on the preamble to the constitution for the newly merged party that was accepted by both delegations.

These one-dimensional views of Greaves are the result of lazy journalism or minimal research. It was necessary to know Greaves socially or to have worked with him on campaigns or other political initiatives over some time to know and appreciate him fully. Similarly, he had infinite time for constituents in Pendle who had a genuine problem that required his attention. Underneath the often-forbidding carapace was a warm and sensitive individual. He was the personal epitome of the application to politics of Newton’s Third Law of Thermodynamics, that ‘for every action there is an equal and opposite reaction,’ and to approach him with a positive and constructive request or suggestion would elicit an equivalent response, but to attack or criticise negatively would be summarily dismissed. Certainly, he could be exasperating from time to time with all his friends and colleagues, but we knew and appreciated his loyalty and solidarity and that he never harboured any animosity towards those he regarded as ‘sound’. What exasperated his colleagues more than anything was the reality of his lack of commitment to a longer-term literary or philosophical project that required significant research and composition. Certainly, the concept of having to revise and rewrite anything was alien to him. The consequences of this trait of ‘moving on’ to another issue was that, although he had considerable influence on Liberal politics over more than fifty years, it could have been so much more.

He took his politics very seriously and, when he did take a break from it, he needed a very different environment. He found the means of escape and of recharging his batteries by taking to the solitude of open spaces. For many years, even after he was ill in 2011, he always spent some weeks climbing, including family holidays in Barèges in the French Pyrenees. and latterly he would holiday with his family on the Isle of Lewis in the Outer Hebrides. He was still hiking and cycling in late 2020. Allied to the geography, he was a long-time fan of the Scottish folk-rock band Runrig. Increasingly he became a rather unlikely family man. He was a patron of the Friends of the Lake District. He took great delight in helping to get the Countryside and Rights of Way Act into law and to be involved in supporting the Marine and Coastal Access Bill. He regarded his work on these latter issues as a way of repaying ‘a little of the huge amount I have got from the mountains and moorlands of this country over so many years as a climber, hill walker, geographer and botanist.’38

- David Steel, ‘The Liberal View’, in Andrew Duff (ed.), Making the Difference: Essays in honour of Shirley Williams (Biteback, 2010).

- Created Lord Evans of Claughton, March 1978.

- Created Lord Tordoff of Knutsford, May 1981.

- See: https://tinyurl.com/rv2j4nru (consulted 18 April 2021).

- Tony Greaves (ed.), Blackpool Essays: Towards a radical view of society (Gunfire Publications, 1967).

- National League of Young Liberals.

- University Liberal Students.

- For a discussion of community politics, see chapter by Stuart Mole in Vernon Bogdanor (ed.) Liberal Politics (OUP, 1983), and Tudor Jones, The Uneven Path of British Liberalism (MUP, 2019).

- Interview with Adrian Slade, 2004, published in Mark Pack blog, 4 June 2012, https://www.markpack.org.uk/32002/tony-greaves-from-angry-young-man-to-simmering-old-guru/

- David Torrance, David Steel: Rising Hope to Elder Statesman (Biteback, 2012).

- Jonathan Kirkup, The Lib-Lab Pact: A Parliamentary Agreement, 1977–78 (Palgrave Macmillan, 2016).

- Adrian Slade interview.

- See: https://www.beemeadowcroft.uk/liberal/liberalismandpower1.html; and David Steel, Against Goliath: David Steel’s Story (Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1989).

- Lancashire Evening Telegraph, 16 Jun. 1987.

- Tony Greaves, ‘Principles of Self-Government in Pendle’, in Peter Hain (ed.), Community Politics (J Calder, 1976).

- Tony Greaves, ‘The Alliance: Threat and Opportunity’, New Outlook, Sep. 1981.

- David Walter, The Strange Rebirth of Liberal England (Politico’s, 2003).

- The Independent, ‘Tony Greaves, archetypal activist, “Hairy man of grassroots Liberalism”’, 12 Sep. 1987.

- Ivor Crewe and Anthony King, SDP: The Birth, Life and Death of the Social Democratic Party (OUP, 1995). See also, Michael Meadowcroft, Social Democracy: Barrier or Bridge? (Liberator Publications, 1981).

- Tony Greaves, ‘A Lifetime in Liberalism: Where do we go now?’, 4th Viv Bingham Lecture, Journal of Liberal History 103, Summer 2019.

- Ibid.

- Tony Greaves and Gordon Lishman, Democrats or Drones? A party which belongs to its members, Hebden Royd Paper 5 (Hebden Royd Publications, Sep. 1987); see also Michael Meadowcroft, ‘Merger or Renewal? A Report to the Joint Liberal Assembly’, 23/24 Jan. 1988, Leeds.

- Rachael Pitchford and Tony Greaves, Merger: The inside story (Liberal Renewal, 1989).

- Michael Meadowcroft, ‘Tony and the Merger’, Liberator 406, April 2021.

- The others were Peter Knowlson, former head of policy for the Liberal Party, Michael Meadowcroft, former Liberal MP, Leeds West, and Rachael Pitchford, chair of National League of Young Liberals. All four were directly elected members.

- Adrian Slade interview, Mark Pack blog.

- Pitchford and Greaves, Merger, appendices 1–4; at a meeting in Leeds on 28 Nov. 2016 Tony Greaves revealed that Shirley Williams had said to him a few days earlier that it had ‘taken her forty years to realise that she was a Liberal’.

- Duncan Brack (ed.), Why I am a Liberal Democrat (Liberal Democrat Publications, 1996).

- Tony Greaves, ‘Audacious – but fundamentally flawed’, Journal of Liberal History, Spring 2001.

- Paddy Ashdown, The Ashdown Diaries: Volume 1, 1988–1997 (Allen Lane, The Penguin Press, 2000).

- Liz Barker, ‘Tony in the Lords’, Liberator 406, Apr. 2021.

- Daily Mail, 25 Feb. 2013.

- Lady Angela Harris, Yorkshire and The Humber Region, Newsletter, 27 Mar. 2021.

- Ibid.

- Daily Telegraph, 24 Mar. 2021.

- Paddy Ashdown, The Ashdown Diaries. Volume 2, 1997–1999 (Allen Lane, The Penguin Press, 2001), entry for 17 Nov. 1998.

- Crewe and King, SDP.

- Quoted in https://www.ramblers.org.uk/news/latest-news/2021/march/lord-greaves.aspxRev.

8 June 2021

Jonathan Fryer, who has died aged 70 of a brain tumour, was a foreign correspondent and writer whose broadcasts from a total of 162 countries made his a familiar voice on BBC Radio. He also wrote about history and lectured on international politics, and spent more than half a century as a Liberal and later Liberal Democrat activist and candidate.

Jonathan Fryer, who has died aged 70 of a brain tumour, was a foreign correspondent and writer whose broadcasts from a total of 162 countries made his a familiar voice on BBC Radio. He also wrote about history and lectured on international politics, and spent more than half a century as a Liberal and later Liberal Democrat activist and candidate.

Jo Grimond brought the Liberal Party back from the brink of extinction. Michael Meadowcroft, former MP for Leeds West, who worked for Grimond in the 1960s, remembers the man and his achievements.

Jo Grimond brought the Liberal Party back from the brink of extinction. Michael Meadowcroft, former MP for Leeds West, who worked for Grimond in the 1960s, remembers the man and his achievements.

Honorary Alderman Douglas Gabb - Dougie to all his colleagues - has died just one month short of his hundredth birthday. To those in Leeds municipal life he was for forty-five years a constant presence on the Labour benches in the Civic Hall council chamber. His other long term political commitment was as Denis Healey's agent in Leeds South East and later Leeds East for the whole of his forty years in the House of Commons. After he had retired from parliament Healey described Gabb as his "best friend."

Honorary Alderman Douglas Gabb - Dougie to all his colleagues - has died just one month short of his hundredth birthday. To those in Leeds municipal life he was for forty-five years a constant presence on the Labour benches in the Civic Hall council chamber. His other long term political commitment was as Denis Healey's agent in Leeds South East and later Leeds East for the whole of his forty years in the House of Commons. After he had retired from parliament Healey described Gabb as his "best friend." Peter Hellyer was one of that remarkable vintage of radical Young Liberals which flourished in the late 1960s and early 1970s. During little more than a five year period this group played a key role in the formulation of a distinctive “Libertarian Left” ideology which they applied to the highly charged issues of the day, including the Vietnam war, apartheid in South Africa, CND and the peace movement and the plight of the Palestinians. Because when faced with establishment intransigence they took to direct action, not least in successfully stopping the 1970 South Africa Rugby tour, they provoked considerable opposition within the Liberal Party hierarchy who felt, probably correctly, that the Young Liberals’ highly publicised actions were losing the party votes and simply did not know how to cope with a youth movement that had considerable momentum, many thousands of members and constantly showed up the rigidity of Labour’s Young Socialists. Also the Young Liberals’ willingness to campaign alongside others who were sometimes in far more extreme and illiberal organisations who agreed with their stance on a specific issue was often much too pluralistic for the party leaders.

Peter Hellyer was one of that remarkable vintage of radical Young Liberals which flourished in the late 1960s and early 1970s. During little more than a five year period this group played a key role in the formulation of a distinctive “Libertarian Left” ideology which they applied to the highly charged issues of the day, including the Vietnam war, apartheid in South Africa, CND and the peace movement and the plight of the Palestinians. Because when faced with establishment intransigence they took to direct action, not least in successfully stopping the 1970 South Africa Rugby tour, they provoked considerable opposition within the Liberal Party hierarchy who felt, probably correctly, that the Young Liberals’ highly publicised actions were losing the party votes and simply did not know how to cope with a youth movement that had considerable momentum, many thousands of members and constantly showed up the rigidity of Labour’s Young Socialists. Also the Young Liberals’ willingness to campaign alongside others who were sometimes in far more extreme and illiberal organisations who agreed with their stance on a specific issue was often much too pluralistic for the party leaders.